With Eyes Unclouded by Hate: Princess Mononoke (1997)

Off its new IMAX rerelease, staff writer Angelica Ng relishes in the lush musicality and visuality of Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke (1997), revisiting its timeless ecological message.

In Princess Mononoke (1997), director Hayao Miyazaki subverts the fantastical slice-of-life elements that dominate his earlier films like My Neighbour Totoro (1988) and Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989). Instead, he presents the audience with a daring new premise: what happens when the enchanted forest of your fairytale dreams actually hates you and wants you dead?

As it turns out, lots and lots of severed limbs.

In full transparency, I did not go into Shaw Theatres’ IMAX release of Princess Mononoke as a Studio Ghibli fan. In fact, my strongest impression of a Studio Ghibli film was watching Spirited Away (2001) in middle school. Needless to say, the graphic beheading of a random soldier in the first ten minutes of Princess Mononoke is a far cry from the pastel-tinted fantasy that I’ve come to expect. “Well, this is certainly not like My Neighbour Totoro at all,” I thought to myself.

In essence, Princess Mononoke captures a longstanding conflict between humankind and nature, revolving around the human settlement Irontown. As the townsfolk deforest the surrounding countryside for profit, they bring the wrath of ancient forest gods upon their village. The film follows Ashitaka, an exiled prince on a mission to undo the curse that has been placed upon him, and San, a human warrior raised by wolves. While initially torn between warring sides, the unlikely duo eventually come together, trying to foster peace between their communities.

What stood out the most to me was the film’s astonishing sound design. The hollow, metallic bellows of Irontown are contrasted with the peacefully rustling leaves and gently rattling kodamas of the forest, immersing viewers in the dreamlike landscape of Princess Mononoke’s world. I particularly loved the use of reverent silence every time the eerie Forest Spirit appears, reflecting the tranquility it represents as the ruler of the forest. That same silence is then twisted into a representation of grief and uncertainty after the Forest Spirit is killed in the film's climactic battle, emphasising the void its absence leaves behind.

Additionally, the soundtrack is absolutely transcendental, and I remain convinced that longtime Ghibli collaborator Joe Hisaishi is one of the greatest composers of our time. The film’s score is filled with grand crescendoes that blend with delicate wind instruments, each part of the orchestra coming together in richly poignant harmony. It feels as if Hisaishi had summoned actual forest spirits to put healing magic into his score – there’s just no other way to explain the masterpiece that is the Princess Mononoke soundtrack.

Not to mention, the IMAX setting truly drove home the scale of this stunning movie, with every scene made more emotionally intense on the huge screen. Tears were shed at the film’s sheer beauty and visual grandeur when the characters’ tiny figures rode across the painted countryside, with “The Legend of Ashitaka” reverberating through the theatre.

This film really solidified for me that Studio Ghibli’s single greatest strength is their weird little creatures. The bizarre but inexplicably charming kodamas are absolutely iconic, with their perfectly blank stare, strange talking noises, and unsettling neck rotations.

Ironically, my biggest issue with Princess Mononoke is Princess Mononoke herself, San. On paper, a warrior princess of the forest raised by a wolf god seems like it would be the most interesting character of all time. And yet…she’s not. I may never understand why San is the titular character and face of the movie, when she is not in fact the main character and rarely acts directly to advance the plot. While San’s position as the bridge between human and nature adds a unique perspective, I find her screentime and interactions with other characters slightly lacking. They fail to solidify her importance in comparison to characters like Ashitaka and Lady Eboshi, whose motivations and actions seem more nuanced. Often, it seems like San simply serves to encourage Ashitaka to act out of love – which is strange in itself, because they’ve barely had one full conversation.

The film was clearly going for the traditional star-crossed lovers route, which is nearly guaranteed to sell tickets, but objectively did not add anything important to the story. The romance elements frequently felt half-baked to me, without much time devoted to establishing the budding relationship. As a result, Ashitaka and San’s relationship pales in comparison to the massive scale of the overarching plot, not serving much of a purpose beyond on-the-nose symbolism. In a film with such significant messages about our relationship with nature and the cycle of violence, a romantic subplot simply feels unnecessary. In fact, the narrative of solidarity between opposing worlds is developed well enough that it would have worked just as well between friends.

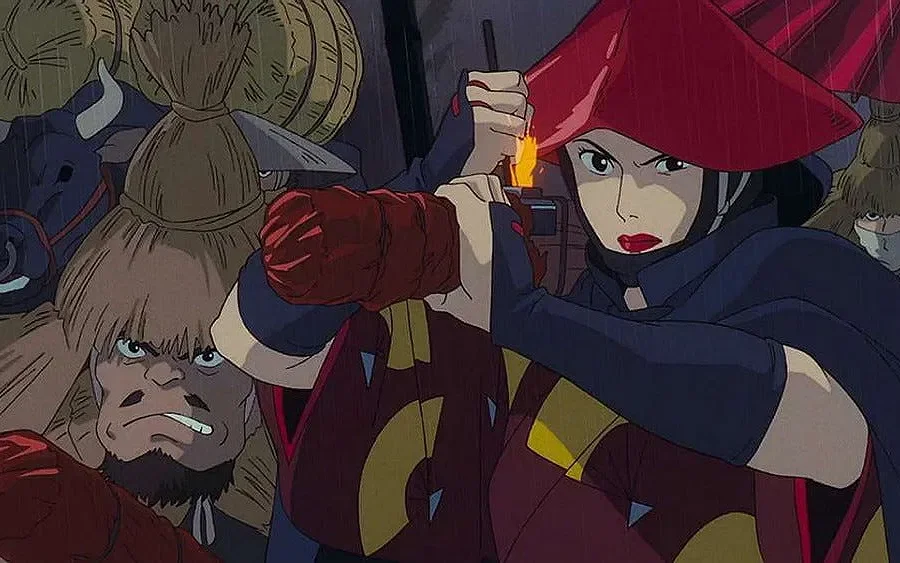

On the other hand, Lady Eboshi steals the show as an exceptionally nuanced and well-written female character. The musket-wielding, ruthlessly intelligent leader of Irontown seems to be the obvious villain at first – she helms Irontown’s efforts to destroy the forest for profit, while pursuing her mission to kill the forest gods, thus clearing the way for further industrialisation.

However, she’s also an intensely sympathetic character. She’s deeply protective and caring towards her people, many of whom she rescued from hardship. They form a gang of misfits and underdogs for whom her rule has offered a second lease of life, each and every one fiercely loyal to her and her cause. It’s easy to understand why she acts the way she does – her agenda is not merely one of selfish profit, but one that aims to improve the lives of her disadvantaged people.

Of course, Princess Mononoke’s two-hour runtime is filled with magnificent scenes of ancient gods traversing the forests and scores of warriors meeting in violent clashes. But for me, it’s when the film zooms in on microscopic moments that its impact is fully actualised. Irontown initially seems cold and industrial, but when Ashitaka enters one of the factories, he finds the women singing in boisterous harmony as they work, giggling and joking together with heartwarming camaraderie.

Similarly, a moment where Ashitaka speaks to the human soldiers after a devastating battle is particularly heartbreaking – one of the surviving soldiers, still trembling, breaks down as he recounts the moment “the world turned upside down”. Even if we’ve mainly been following the forest’s side thus far, it’s a striking reminder that nobody really survives a war unscathed.

In addition, while the theme of human versus nature has been frequently explored in film, Princess Mononoke is one of those rare films that truly explores the abject horror of nature as an immense and sentient entity, dwarfing the humans around it while exacting revenge. The forest becomes a violent and destructive being, seething with rage. Featureless apes appear, hellbent on eating humans as revenge, and masses of furious boars advance upon the humans, forming a moving flood of bodies. Hatred and trauma manifest as squirming, pulsating masses of earthworm-like creatures that gradually consume the forest gods, blood pouring out of the possessed deities’ orifices. This visceral imagery forces audiences to confront not only the damage humans have done to the forest, but also the corrupting nature of this hatred, as an unstoppable force that leads to the painful deaths of the forest’s previously benevolent deities – a clear sign of the destructive impact of the war between the forest and Irontown.

As one of Miyazaki’s most complex and violent films, Princess Mononoke is a necessary but tough watch at times. The film depicts the horrors of war with unflinching solemnity — there are no true victors on either side, and everyone suffers devastating losses. Ashitaka battles throughout the film with hatred that manifests as a literal curse, reflecting just how easy it is to let anger fester and cloud our decisions. He struggles against all odds to defeat the violence that threatens to literally consume him, spreading across his body and controlling his actions. It’s an apt metaphor for the inner battles many of us fight, and the difficulty of choosing to strive for peace, even in the face of injustice and hardships.

While it’s a tad depressing that the film’s themes are still so relevant nearly thirty years on, it’s also a sign of Miyazaki's extraordinarily clear eye. He seems to acutely understand the realities of the issues we face today, what viewers need to hear in order to make it better, and how to convey his messages in a way that lingers long after the credits roll. The film’s ambiguous ending creates a sense of tenuous balance – much like in real life, it’s up to us to fill in the blanks and decide what happens next.

Princess Mononoke reveals with sharp clarity that there are demons in all of us, rotting us from the inside out, and it’s only by letting go of this rage and hatred that we can move forward. It’s a tough pill to swallow even decades later, in a time where there’s so much to be angry about. Still, the film seems to retain its confidence in the human race, and the world as a whole: as long as we’re alive, the fight isn’t over, and we can still make things right — as Miyazaki puts it, with eyes unclouded by hate.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021