A Very Stale Breakfast at Tiffany’s

Staff Writer Angelica Ng offers a different perspective of the idyllicism in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961).

Despite the film being lauded as a classic romance, evoking the enchanting nostalgia of old Hollywood, I remain convinced that Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) is possibly the least romantic romance movie I have ever seen. It’s tolerable as a casual and mindless watch, with beautifully coloured shots and a dreamy portrayal of life in bustling 1960s New York. Yet, despite being based on a short story of the same name by Truman Capote, it can be considered a disgrace to its source material (Capote himself once famously called it the “most miscast” movie). My main gripe with the film is the deeply problematic relationship between the two leads, Holly Golightly and Paul Varjak. Coupled with a main character who’s seen as a joke by the entire cast, Breakfast at Tiffany’s certainly does not stand the test of time.

From watering house plants with alcohol, to accidentally lighting hats on fire with her cigarettes, it’s clear from the start that Holly Golightly is one of the original Manic Pixie Dream Girls. To me, this is a character trope that should stay firmly rooted in the past. I like to believe that modern audiences are steadily losing patience for these female characters — lovably quirky and tragically one-dimensional, yet somehow just unique enough to change the trajectory of her boring love interest’s life forever. Film critic Nathan Rabin, who coined the term in 2007, referred to the trope as a character who "exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures” – a description that fits Holly to a tee. She’s portrayed as drifting aimlessly through life, spontaneously making decisions with a naive but impressive level of confidence. While her chaotic nature can begin to grate on the viewer’s nerves, Holly’s saving grace is her uniquely free spirit. However, the film ultimately still disappoints in its portrayal of Holly, who oscillates between fiercely independent and annoyingly immature.

It’s fascinating that she exhibits a fair amount of self-sufficiency for a woman in the 1960s, and has created an entirely new life for herself. Her ex-husband bemoans that her place “is with her husband, her children, and her brother,” yet Holly seems able to successfully shirk these traditional caretaker duties. After all, she escaped life as a housewife in the countryside, married to a man old enough to be her father. She transforms into a glamorous society girl in New York City, drinking and smoking with gay abandon at wild parties, and charming men out of their money with only her good looks and endless charisma. She’s shrewd and charming, easing her way out of trouble with a sweet smile. “It’s a mistake you always made, Doc, trying to love a wild thing,” Holly tells her ex-husband as she bids him goodbye.

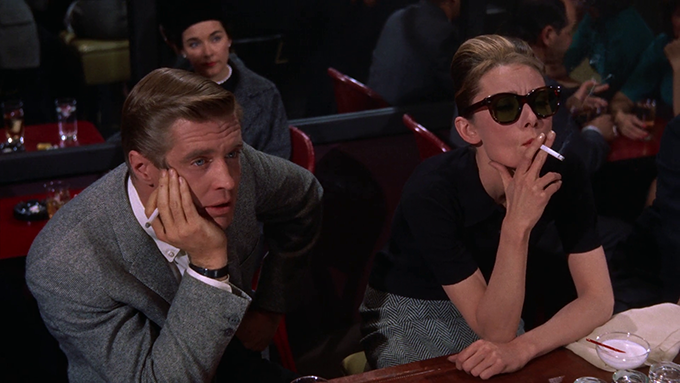

Yet, much like her society, the film itself rarely takes Holly seriously. Despite setting up her long journey to her perceived freedom in New York City, she is still shown to viewers as a petulant young child who doesn’t know any better than the men around her. Male characters constantly refer to her as “kid”, “little girl”, “child”, or “baby”. In moments of insecurity, she bemoans that she doesn't know who she is, and rebels weakly against Paul’s clear disapproval of her actions. Her efforts at rebellion never seem to get very far, consisting of impulsive actions and emotional outbursts that serve only to diminish her character’s previously-established strength. It seems as though, much like the film’s characters, we are meant to shake our heads with an indulgent smile and dismiss Holly as a childish ditz, prone to flights of fancy.

Hence, it comes as no surprise that the romance at the film’s core is thoroughly unrealistic, pairing free-spirited Holly with guarded and stoic Paul. Instead of a sweet opposites-attract romance, Holly and Paul clash frequently, owing to their contrasting personalities and worldviews. Paul’s paternalistic disapproval of Holly is apparent throughout each interaction, reinforcing her portrayal as impulsive and immature. In a fiery exchange, Holly asks “Do you think you own me?”, to which Paul replies “That’s exactly what I think”. While discussing his feelings for Holly, Paul explains, “I can help her, and it’s a nice feeling for a change.” It’s hard to see Paul as being any different from the countless men who feel entitled to Holly. They each regard her as a “wild thing” to be tamed, a damsel in distress who simply needs the guidance of a strong man – she just doesn't know it yet. It’s wildly frustrating that despite subverting gender roles of her era and achieving a substantial level of independence, Holly still ends up throwing all of this away to settle down with Paul. Holly loses her freedom and potential as a character, while Paul gets to improve through her influence. He’s motivated to write for the first time in five years after meeting her, and his writing is almost immediately met with surprising commercial success, while Holly’s dreams and goals are torn down one by one.

The film culminates with a final confrontation between the two lovebirds, or rather, five solid minutes of Paul berating Holly with lines like “You know what’s wrong with you, Miss Whoever-You-Are? You’re chicken. You’ve got no guts.” After Paul storms out, abandoning Holly in a taxi, she gazes wistfully at a ring Paul gave her, and ultimately chases after him in the pouring rain. The ending contradicts every bit of her personality as shown thus far, and is entirely unfair to a character who’s already largely well-developed on her own. Why should Holly settle for a man who clearly has no respect for her? Who needs enemies, when you have love interests who deliver brazenly arrogant words like “I love you – you belong to me”?

The answers are obvious as the film falls back on a tired cliché – romantic love is the only thing that can fill up the gaping emptiness in Holly’s delicate heart. Breakfast at Tiffany’s is torn between being a study of a uniquely eccentric character, and a traditional romance movie with a happy ending (forcefully stuffed into the last five minutes). This indecisiveness serves to create a thoroughly unromantic and unsatisfactory viewing experience, leaving me more horrified than enthralled at the supposed “happily-ever-after”.

However, is it fair to criticise a film for not reflecting modern values, if these standards barely existed at the point of the film’s inception? For me, a massive obstacle in crafting a fair critique of Breakfast at Tiffany’s has been its time period – the film premiered in 1961, over 60 years ago, and it certainly shows. However, while issues like misogyny and racism may raise red flags for an audience in 2024, the same logic cannot always be applied to well-loved works created so many decades ago. To compare the film to modern works is to brush aside its social and cultural context, viewing it in a vacuum of modern morality while failing to consider perspectives of audiences and filmmakers of its time.

By accepting classic films in their original contexts, we are better able to understand these bygone eras, and can begin to truly grasp how far we have progressed. Breakfast at Tiffany’s continues to have varied impacts on pop culture and modern audiences of today. In using the highly-debated term “bygone era”, I hope to shed light on how the ideologies of that era have developed and shaped the way we now view and interact with gender, independence, and romance.

Hence, the elusive search for true “timelessness” cannot always be the first priority, and a film need not necessarily be #woke to have value – after all, cinema functions as a reflection of our society, complete with all of its flaws and imperfections. Modern audiences must inevitably accept that Breakfast at Tiffany’s cannot help but exist as a product of its time. However, certain elements of good storytelling will never change, no matter the decade: a solid plot, dynamic characters, and well-developed relationships, to name a few. This is why even after setting aside issues of morality, the film still leaves much to be desired, particularly when compared to films from the same era.

Fans of Breakfast at Tiffany’s often argue that the ending is a deeply moving conclusion to the film, reflecting Holly’s development as a character. While initially in denial about her true desire to settle down and belong somewhere, the ending can be interpreted as Holly managing to finally find someone who will provide her with the loving home she’s always wanted. She eventually comes to realise that people can indeed “belong” to their loved ones, in a way that’s less of staking one’s claim on another human being, and more of taking care of and remaining loyal to someone you love. However, if this was indeed the intention behind the film’s conclusion, it falls flat in its execution and fails to convey a clear and logical journey for Holly’s character.

By the end of the film, Holly still appears far too “wild” and free-spirited, making it seem as though Paul is forcing her into the role of a classic love interest through his overbearing nature and unrealistic expectations. In my opinion, the film fails to balance character study and feel-good romance. Despite the filmmakers’ valiant efforts, the differences between these two sides of the film are irreconcilable – even after the events of the film, the two leads are still too drastically different, unwilling to bend to each other’s romantic expectations. This makes the forced “happily-ever-after” thoroughly unrealistic, and the characters hardly appear to be entering a healthy relationship in which both parties respect and accept each other for who they are.

Personally, I believe this disconnect occurs because Breakfast at Tiffany’s should have never been a romance film in the first place. Despite being an adaptation of Truman Capote’s novella of the same name, the film's significant departure from its source material inevitably leads to many of its plot and character flaws. The novella itself focuses heavily on Holly’s idiosyncrasies and her impact on the people around her. In fact, I’ve always seen it as less of a traditional romance between characters, and more of a love letter to life itself. The novella never forces an overly romanticised portrayal of Holly – there is no real romance between Holly and the narrator (replaced by Paul in the film), who instead strike up a fragile friendship as they navigate their hardships together. In fact, a character states in the very first chapter that he never thought of Holly in a romantic or sexual manner, saying instead that “You can love someone but not want them in that way”.

Another character establishes that Holly’s uniqueness is a part of her through and through, telling the narrator that “You can’t change her”. Holly is much bolder and more confident in the novella, even directly accusing the narrator of seeing himself as better than her, an undercurrent that was never fully explored in the film. She’s much more capable of holding her own, a far cry from the childish figure in the film who ends up relying on Paul for emotional support. To draw a direct comparison between the film and novella, both end with Holly revealing her more vulnerable side, afraid of both being trapped by others, and of ending up completely alone. However, the film chooses to end with Holly pursuing a questionable relationship with Paul, while the novella focuses on her freedom and independent decisions.

In a tender moment with the narrator, she candidly expresses her fear of not belonging, yet eventually still leaves to make her own way in the world. Her final fate is left open to interpretation, and the novella concludes with the poignant line: “I hope Holly has found a place where she belongs, too.”

To be fair, it’s not difficult to see why the filmmakers defaulted to the romance genre instead of pursuing a faithful adaptation. For a 1960s audience, a traditional romance film with attractive leads and a heartwarming ending would almost certainly be more successful than an abstruse work of literature. Still, a desire for commercial success and mainstream recognition is no excuse for underdeveloped characters and half-baked relationships in film, as evidenced by other famous works in the romance genre from the same era.

The Sound of Music (1965) is a classic example of a wholesome romance film, complemented by iconic songs and legendary performances by main leads Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer. Yet, underneath the film’s lighthearted playfulness lies a solidly developed romance, with gradual development of both leads accented by palpable chemistry. Whether it’s maturing from an initial naivety and lack of confidence, or learning to be more caring and emotionally vulnerable, both characters grow and learn from their love interests throughout the film. They accept each other without forcing the other party to change, with love transforming their perspectives and motivating them to become better people. The film effectively portrays what I view as the true ideal of a romantic relationship – seeing both someone’s strengths and flaws, and choosing to love them regardless.

On the other hand, not all romance films must end with a traditional happily-ever-after in order to be successful. Roman Holiday (1953), another iconic Audrey Hepburn film, is an example of a romance in which the leads never end up together. Despite a whirlwind, fairytale-esque love story between a princess and a reporter, the film wisely allows its leads to go their separate ways in the end, left with merely the precious memories of their time together and their indelible impact on each other. Instead of forcing a contrived relationship, Roman Holiday demonstrates that a romance film has the potential to be even more emotionally impactful when its characters aren’t shoved into a “perfect” relationship, when such an ending simply isn’t a feasible or effective conclusion to their stories.

Premiering within years of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, both of these renowned films feature thoroughly well-developed romantic plots, while experiencing impressive box office success. This makes it even more disappointing to me that Breakfast at Tiffany’s central relationship falls flat, in a time when so many other films of the same genre featured far more believable and emotionally fulfilling romance elements.

Personally, I believe the heart of this debate lies in what one can accept in a film. Perhaps some can excuse a shaky relationship if a film is beautiful to look at; perhaps some can overlook a questionably developed character if she’s as iconic as Holly Golightly. In light of both Capote’s magnificent source material, as well as the legendary (and unproblematic) films of the same era, I remain unable to truly enjoy Breakfast at Tiffany’s without experiencing an intense urge to stand up and start shouting at the screen. I now often find myself wondering what it might have been like to sit with Truman Capote (another passionate hater and a rather chaotic figure in his own right), and simply gossip about this questionable adaptation together. Would he agree with my points, or see the film in a different light? While I will sadly never know the potential joy of trash-talking this widely loved film with the creator of its source material, debating the film with my very alive and contactable friends has been incredibly fun nonetheless. No two people will view a film in the same way, and to me, that is the magic of film – something that will never change for as long as films continue to be made.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021