PFF Review: Finger on the Pulse–How Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001) surges through Cloud (2024) & Chime (2024)

Leading up to the Singapore premiere of the 4K Restoration of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001), staff writer Adrian Ho exorcises the concerns of the director’s preternatural filmography: the malaise of loneliness, and the banality of violence at the heart of modern technology.

Y2K, crop tops, low-rise jeans, flip phones, and MP3 players. At the turn of the century, all these trends were absolutely unavoidable, and so was the rise of the J-Horror sub-genre in film.

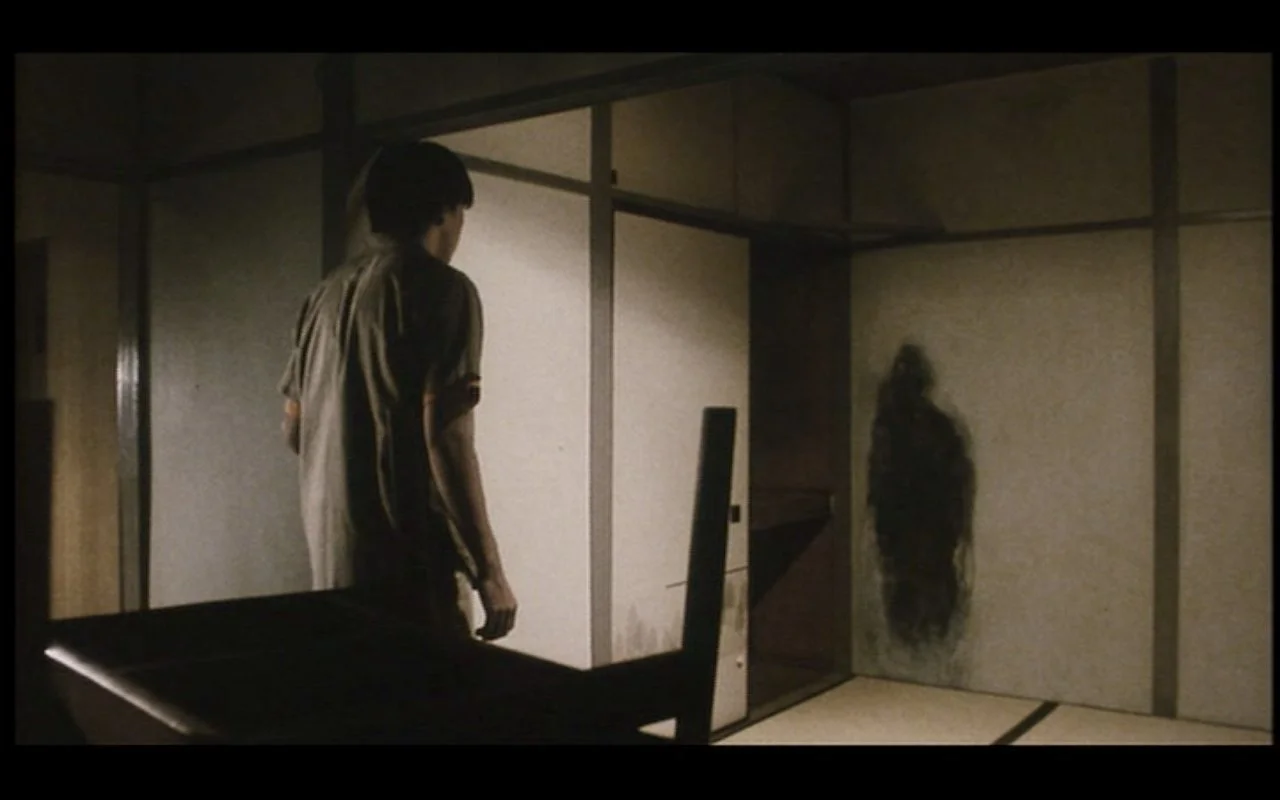

While the genre began in earnest in the eighties, it exploded into popularity with Hideo Nakata’s iconic The Ring/Ringu (1998) – based on the titular 1991 novel by Koji Suzuki – which conflated the seemingly disparate genres of the supernatural and machinery. The film helped unearth nascent fears around technology, with its narrative driven by a mysterious videotape that causes a series of teen deaths. While the sub-genre is rightly recognised for its association with vengeful spirits – the iconic Sadako, with her pale face and long black hair in Ringu – which can be traced back to the horror fiction of the Edo and Meiji period of Japan, there was also a strain of J-Horror particularly in the late 1990s and early 2000s, that redirected their fears towards technology.

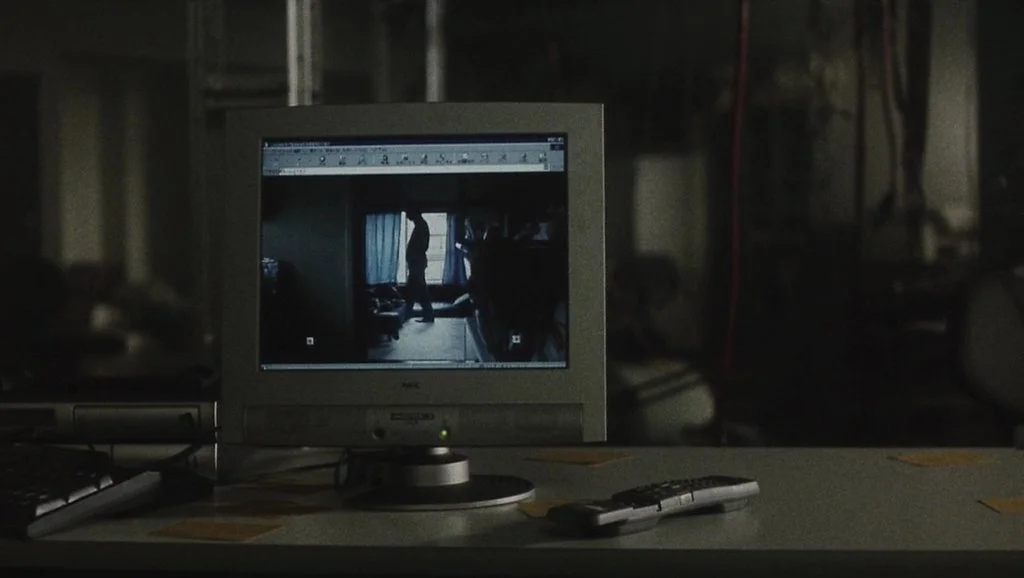

Pulse (2001), Kurosawa’s self-professed knockoff of Ringu, latched on to the tantalising liminality that technology offered. As a space which was then undefined, at least to the layman, the digital world offered a novel stream of virality in the newfound interconnectedness that defined these technologies. It was an effective combination that allowed for the co-opting of the technological space as a digital seedbed for the supernatural, while immersing the audience through the breaching of cinematic boundaries – here, the screen which traditionally acted as safeguard for audiences became the portal that instead bridges them closer to terror, allowing for audiences to share in the fate of the on-screen subjects.

In Pulse, the internet is reimagined as a malevolent force. A nebulous plague spreading isolation and loneliness, reducing affected youths to little more than a smudge of black on walls. The imagery inadvertently recalls the atomic devastation of Hiroshima, and the enduring psychological effects of nuclear anxieties are certainly at play throughout Kurosawa’s film, though reshaped into a more insidious and deadening force. Pulse captures the anxieties of the new millennium, of the existential uncertainties associated with this time of great change. The promise of the internet as a conduit for greater connectivity has turned into a great irony, reflecting instead the fear that people can’t ever truly get close to one another, no matter the medium or the tools. The technological space then, isn’t simply just a motif to project the supernatural on, but these supernatural elements seem to also reflect the fears of the people within the technological era – of the weakening social fabric, the allure of personalised solitude and the failure of connection.

In the twenty-odd years since the release of the film, Pulse has become the authoritative film on loneliness in the 21st century as the domineering presence of technology casts its long shadow over our daily lives. In fact, it isn’t much of a stretch to say that we probably spend more time in front of the computer or staring into our phones than we do anything else. Even if one were to avoid the toxic spiral of doomscrolling on social media, online culture is still inextricable from the work we do, the relationships we foster, and most definitely, the purchases we make. Perhaps that is why, in his latest, Cloud (2024), Kurosawa has shifted his attention to a seemingly innocuous side of the internet – e-commerce.

The film follows Ryosuke Yoshii, a hustler who jumps on every opportunity to make a quick dollar; a scalper, a cockroach of the internet. He isn’t really interested in what he sells, as long as it does, indeed, sell. For Yoshii, life has been reduced to a string of numbers, a game defined by the end of a bank statement. Much like his affairs, his interactions are mainly transactional, and devoid of emotions. Yoshii can come off as aloof or carried by a calm confidence, but in a way that is absolutely infuriating for the people around him, and which elicits resentment from others. That resentment is compounded online, as his internet hustle leaves a barren path of scorned users behind him. What lies in wait for him is comeuppance and what follows an initially tense atmospheric thriller is a revenge picture in the form of a bullet-riddled shoot-’em-up.

Cloud doubles as both a moral tale and a sobering depiction of the deep onset of late-stage capitalism, set amidst the collapsing boundaries between the digital and physical spaces within modernity. Animosity travels between these boundaries and the internet is displayed as a catalyst for the worst of human behaviour, stripping away the veneer of civility and morality with its veil of anonymity. The malevolent force of Cloud, unlike its supernatural cousin in Pulse, is instead revealed to be the numbing consequence of capitalism and commodification, moved by the impulse for revenge.

In this way, Cloud serves as an intriguing extension to the existential fears of Pulse, where the failure to connect isn’t merely hypothetical, but reality. The collapse of society continues with an apocalypse of the heart, of the malice which sits within, driven by the mechanisation of the internet and the mercantilism it inspires. Technology is the familiar culprit between the two films, staged here as a lawless battleground that breeds hostility, bringing strangers together through contempt for the inequalities experienced. It’s a caveat to the search for interconnection in Pulse, with an implication that vitriol alone is the animating impetus for modern connection.

In the same year, Kurosawa also released Chime (2024), a mid-length feature that feels like it’s also in conversation with both Pulse and Cloud. The film follows a culinary teacher whose outwardly peaceful life is disrupted by the repeating sound of a chime. The chime is introduced through a student in his class, who first comes off as distant, if not a little odd, and who later confides in the instructor of a nagging sound in his head, of a brain half-replaced by machine. The presentation of this narrative device as an inexplicable and invisible force which drives the accursed into frenzied bouts of violence recalls the malevolent and omniscient force of Pulse. However, rather than exist within the liminal space of the supernatural, the aural motif, rooted in a common noise in the aural landscape of the city, functions as a nagging reminder of how contemporary life wears people down.

With Chime, Kurosawa charts a world descending into madness as an alienated population falls apart from the inside-out. The inescapability of technology in our lives, with its constant pinging – of texts, calls and emails – has permanently altered our brain chemistry, keeping us constantly on edge. The ubiquity of technology and its prevalence in our lives functions like a chime in the distance, sometimes unnoticed, but always there, omnipresently.

The director had previously described Cloud as being about violent incidents that “occur for seemingly no reason whatsoever”, that when investigated, becomes apparent that these occurrences are fueled by modern systems. Much of the same can be said about Chime, which investigates how contemporary society fails in the upkeep of social bonds, furthering the message of alienation and loneliness first examined in Pulse – like many auteurs, Kurosawa’s filmography seems to always be in dialogue with itself.

In these three films, Kurosawa seems to actively be taking the temperature of the zeitgeist, and in putting these films directly alongside one another, one can see how a prevalent culture of isolation and alienation, captured in the inseparability of technology in our lives – as forewarned in Pulse – has lead to an apocalypse not too far in truth from the one depicted in that film. The internet was introduced as a tool for greater connection, but Pulse, in its suspicion, presciently captured the irony in how it only served to personalise our isolation and solitude. The original sin of the internet is then explored again in Cloud and Chime, who in their own ways, draw insinuating connections between the rootedness of technology in our lives and the degradation of the social fabric and the individual.

Pulse (2001) is screening at Oldham Theatre on 25th October (Saturday), as part of this year’s Perspectives Film Festival: Breakthroughs in Cinema, organised by NTU WKWSCI, marking the Singapore premiere of the film’s 4K Restoration. Get your tickets while you can!

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021