La Haine is not a Black-and-White Film

Staff Writer Agastya Polapragada ruminates on what makes La Haine (1995) such a beloved classic in the cinematic world following NTU Film Society’s screening of the film earlier this semester.

Matthieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) translates to ‘hatred’ in English, which is unsurprising considering that the fiery emotion dominates every single scene in the film (except for one fairly random break dancing scene). Kassovitz was inspired by an incident wherein a police officer and a kid were arguing during an interrogation, and the officer pulled out his gun to scare the kid, only to accidentally shoot him. La Haine was born out of his curiosity to understand how such a deep hatred could come about and what had happened between the police officer and the youth during the day leading up to the violent incident. It is a film that concerns itself with themes of violence, racism and police brutality from the perspectives of three young men who come from the projects, which are impoverished and dangerous areas.

It begins with a prophecy disguised as a short story, one that applies not just to its main character, Vinz, but to most of the kids who grow up in the projects. The story is told as such: “There is a man who falls off a skyscraper, and on his way down, past each floor, he keeps saying to reassure himself, so far so good, so far so good. But how you fall doesn’t matter. It’s how you land!” We are immediately prepared to witness the ill-fated path the film’s characters will tread, and are ready to soak in the heaviness that comes with such a story.

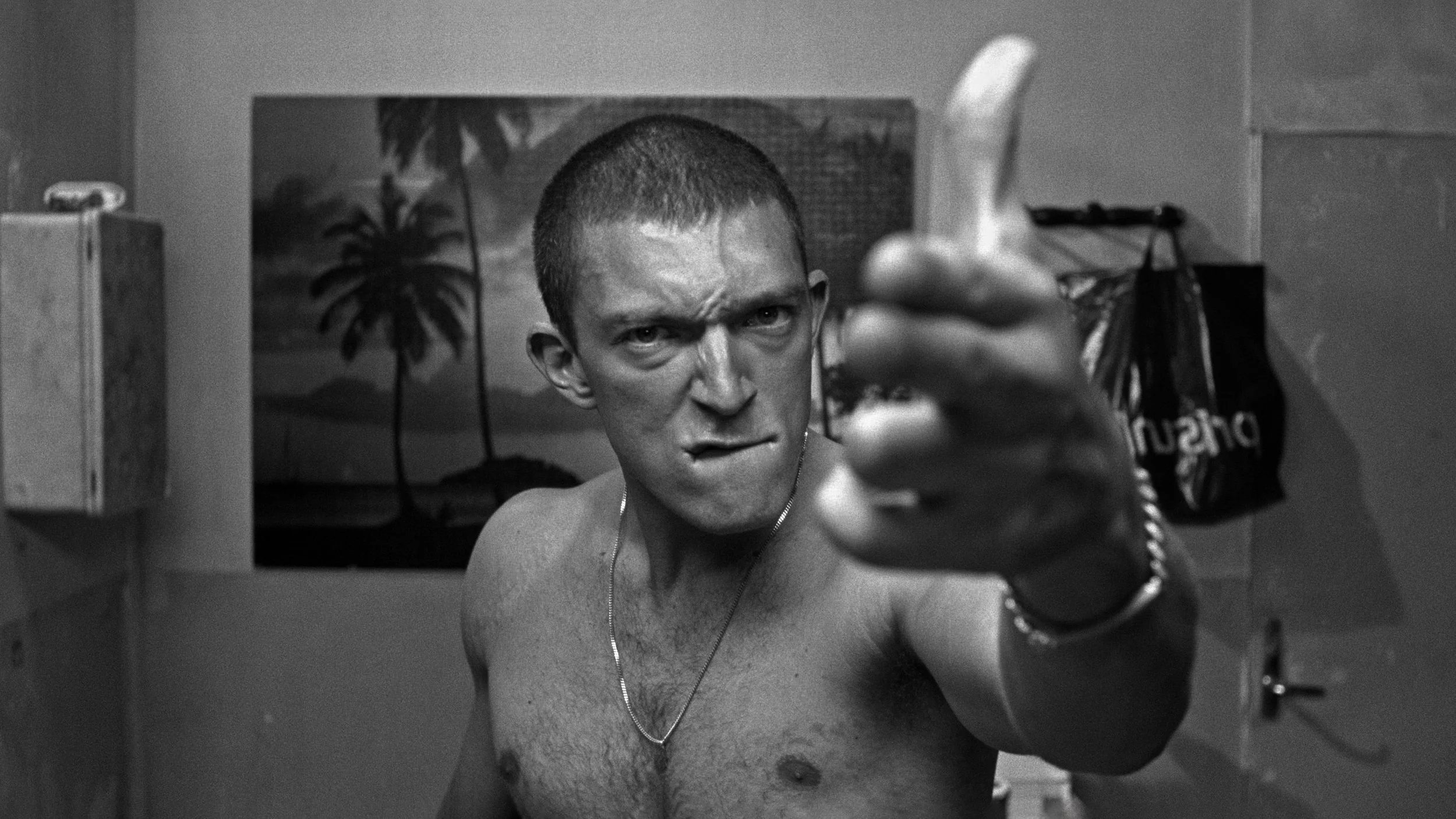

La Haine follows 3 main characters who are all very intricately crafted. First, we have Vinz, an eager young man who’s deeply antagonistic towards the police and wants to become more extreme in his rebellion against them. Then there’s Hubert, who wants to keep his head down, succeed, and leave the projects. And lastly, there’s Said, who’s not particularly concerned about anything other than his immediate gratification and making it through the day. The characters leave a deep impression on the audience because they are not just archetypes but carefully thought-out personas that are essential in driving the film’s themes. Instead of relying on a fast-paced plot or a typical narrative structure, La Haine’s magnetism is entirely dependent on the push and pull between its characters.

Despite how the film foreshadows its ending thrice, everyone seeing it for the first time is still shocked when it ends as it was prophesied and the credits roll, as my 15-year-old self was. I think this can be credited to the film’s expert use and withholding of tension, and how it does not let viewers feel any true emotional catharsis until the movie ends.

Diving into this, La Haine is famously structured like a time bomb. With frequent cutbacks to the time “10:38.. 12:43..” accompanied by an unnerving ticking sound, it is relentlessly suspenseful and constantly confronting us with the precipice of danger. The audience cannot escape the nauseating anxiety of what has been foreshadowed throughout the film. Will Vinz cross the line and kill someone? Will he get himself killed, and will his friends get dragged into it? Yet, the movie never takes the plunge until the end, or it risks desensitising the audience to the possibility of a bad outcome. Instead, it calms and pacifies its audience through humour and misdirection. This can even be seen in the character arcs throughout the movie. Vinz and Hubert fight earlier in the film, creating tension, but they reconcile near the end, giving the audience a false sense of security. Perhaps a good ending is possible after all.

Vinz also proves to the audience that he can’t cross the line and isn’t capable of killing someone when he humbles himself by handing his gun over to Hubert. In this regard, he chooses the right path, even if it is late into the story, but that does not matter to the prophecy. As La Haine has warned viewers since the beginning, what matters is how you land. What obligation does the narrative have to reward Vinz for making a good decision when he has been falling since the beginning? So despite all this reassurance, the ending is no different.

This begs the question, what makes the ending so unavoidable? Why does it feel like the fates of our characters are inevitable? I find that this ties into the film’s more fundamental theme of how people born into poverty are institutionalised into believing it’s fated. The desire to have a nicer life is absent from our characters. Their ghettos are isolated, and the city of Paris and its better services are inaccessible to them. Ending their poverty is seen as such a fantastical, intangible goal that it’s a notion not worth considering. Vinz’s obsession with wanting to exact vengeance on the police, even if it's to no end, is not the result of him being inherently violent, but because he was socialised into thinking that it is the only form of power he has. Ultimately, it is difficult for cycles of violence to be broken by people who cannot see a better version of themselves, but just a member of their violent environment.

In the middle of the film, a character outright lays out the plot through a parabolic story. Our three main characters, mainly Hubert and Vinz, are arguing in a restroom. Suddenly, a short, old man bursts open his door as he flushes the toilet and buckles his pants. Having heard the debate, he speaks immediately, saying, “You believe in God? That’s the wrong question. Does God believe in us?”. An incredibly poetic line, it doesn’t just force everyone to pay attention to what the man is about to say, but perfectly draws out the feeling of being abandoned and scared.

He then continues to tell a story about his old friend Gruwalski and their time together in a Siberian work camp. He talks about how when you were on the train and needed to relieve yourself, you’d have to wait for it to stop for water. Gruwalski was embarrassed about doing that in front of everyone else, and the old man teased him about this. One day, he took his teasing too far, and Gruwalski went off on his own after they got off the train, and when the train began to leave, he was still behind a bush with his pants down. Gruwalski ran to the train holding his pants with his hands, but as he reached for the old man’s outstretched hand, his pants fell to his ankles. So he would reach back down to pick them up, and then reach for the old man’s hand, repeating the cycle, ultimately being left behind and freezing to death.

This story perfectly mirrors Vinz's need to do what is practically right and his desire to be seen as a real gangster. Just like how Gruwalski's desire to avoid embarrassment cost him his life, Vinz’s desire to act tough ultimately got him killed, too. Though both situations could be resolved with an improvement in material conditions, the point of the old man’s story still stands. His warning was futile, and Vinz pushed his bad habits to the most extreme ends until he couldn’t anymore.

The technical elements are also masterful in aiding the film’s tense and naturalistic feel. Much of the film’s dramatic vibe stems from its high-contrast black-and-white cinematography and its effective use of shadows. The camerawork also maintains the perspective of each scene really well. If the scene is more intense, the camera moves very close to the characters and adopts a claustrophobic stance, favouring whichever character is commanding the scene. On the other hand, the film’s naturalism results from the absence of an original soundtrack and the decision to insert real documentary footage at the beginning of the movie as a tone-setter. This results in the viewer treating the events of the films as if they were happening in the world rather than as a fictitious story. All of this extracts a sense of seriousness from the audience towards the social issues discussed and leaves a lasting impact.

La Haine is a film that has so much to say. The themes I have covered so far barely scratch the surface. There is so much more to explore–I have completely left out its heavily racialised elements in portraying ghettos as one big melting pot and the bigotry of the police. Nonetheless, to me it is undoubtedly one of the best-written, shot, acted and uncompromisingly unique films ever made.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021