Love in the Materialistic City: Unpacking Modern Romance in Materialists (2025)

This review contains spoilers for Materialists (2025)

From the Italian streets of Roman Holiday (1953) to the roads of Hong Kong in Comrades: Almost a Love Story (1996), it seems that filmmakers have always been interested in exploring the dynamics of romance in the modern city. In a way, it makes sense. In Lost in Translation (2003), the reticence of Tokyo’s city dwellers is used by Sofia Coppola as an instrument to advance the two leads’ romance, while Spike Jonze employs the glamorous-yet-distant lights of a futuristic Los Angeles to feed the protagonist’s loneliness in his response film Her (2013). Despite the hustle and bustle of city life, we might, ironically, feel lonelier and more isolated instead. In a larger sea of people, our lives feel more insignificant.

And there’s no other big city in the world like the Big Apple, which has become Hollywood’s darling for many modern romance settings. New York City serves as the backdrop of Celine Song’s sophomore effort Materialists (2025), which follows successful matchmaker Lucy (Dakota Johnson). Lucy finds herself caught between two men from extremely different backgrounds – wealthy financier Harry (Pedro Pascal) and her struggling actor ex-boyfriend John (Chris Evans) – and throughout the film, audiences are left to wonder who she will choose.

As a professional matchmaker, Lucy should know all there is about love and marriage.

To her, marriage is a business contract, and it “always has been”. That is exactly what she tells Charlotte, one of her clients, when she confides in Lucy about the absurdity of choice in modern marriage. “It's not like I'm getting married because I need to forge a relationship between two kingdoms. It's not like my family needs a cow,” Charlotte tells Lucy, “I chose this. I chose to marry a man.” In central Manhattan, where every street corner is a stark reminder of modernity, Charlotte seems to find it ironic that a contemporary woman, free of traditional expectations, would still willingly choose to partake in such a traditional custom. In our modern world, true romance seems to take precedence over economic or social imperatives – but as the movie progresses, Song seems to challenge if this really is the case.

Lucy tells Harry on a date that matchmaking is just “math”, and looks out for the following when she’s matching her clients: similar economic backgrounds, politically aligned, well-matched in their attractiveness, and similar upbringings. On the surface, to treat love with the indifference and calculation of a science might sound superficial and awfully orchestrated, but it seems to work. Lucy, at this point, has successfully coordinated seven of her clients’ marriages – but yet, when she tries to apply these same rules to her own pursuit for love, her rose-tinted glasses begin to crack.

Throughout the film, Lucy seems to convince herself that she has to be with Harry, what people in her industry would call a “unicorn”. Harry has the looks, the physique, the money, and the personality, someone clearly hugely desirable. And despite their incredibly different backgrounds, Harry tells Lucy that he isn’t swayed – he’s not looking for the prettiest woman, but instead for one who is smart, trustworthy and respectful. “Material assets are cheap. They don’t last,” he tells Lucy. “I want to be with you for your intangible assets. Those are good investments”. To Lucy – and to viewers alike – Harry’s a total catch. Who wouldn’t grasp at such an opportunity? And yet, Lucy having reservations seems to hint at a certain fallibility of or skepticism of her very own methods.

On the other hand, however, Lucy and John’s history is a much less glamorous romance. Flashbacks to their past relationship reveal that she and John were both struggling, aspiring actors from low-income, dysfunctional families, having to live with cramped apartments, roommates, “shitty car[s]” and “shitty restaurants”. In a disagreement with John over parking fees, Lucy walks out of the car and breaks up with him, saying: “it's not because [they are] not in love; it's because [they are] broke”. Clearly, love and material needs seem to be in tension with one another – it is not enough for only one to be met.

In another scene where Lucy finds out that Sophie, one of her clients, was assaulted on a date with a man she set her up with, her perception of love being an easily-engineered concept fractures even further. Lucy becomes more disillusioned – she disparages her clients and openly criticises them for their unrealistic expectations. When one of them sends a complaint calling her agency a “scam”, she cedes to its apparent truth: “We promise them love, and then we just give them bad dates with morons and criminals.”

Nonetheless, she only mentions her work troubles to John, and does not confide in Harry at all. After all, her intimacy and familiarity with John seems to trump his material deficiencies. But this reality – that love might endure over the superficial – Lucy has difficulty accepting. When Lucy and John reconcile, she catches herself when they almost kiss. Having climbed the social ladder thanks to her career, Lucy is granted access to high society, to men like Harry, a rare opportunity for people of her upbringing. To get with John is to turn her back on her newfound affluence and social standing, things she worked so hard to achieve. As such, despite the reality that she might just prefer John over Harry, Lucy is not willing to plunge back into a relationship with him and to have financial issues threaten their romance again.

But there is one thing that is different now. While John still lives in the same apartment and works odd jobs to support himself, Lucy is considerably wealthier. Their relationship might just have a chance to last now that there is less financial strain. Money was the only reason why they stopped seeing each other, even though it seemed like they were meant to be, and it just goes to show how much money means in the materialistic city. As such, Song concludes that we, as consumers of the capitalist system, cannot escape the reality of material value. Materialism will always find a way to seep into our daily lives, no matter how hard we try to reject it, as money will always be the ticket to survival in our modern society.

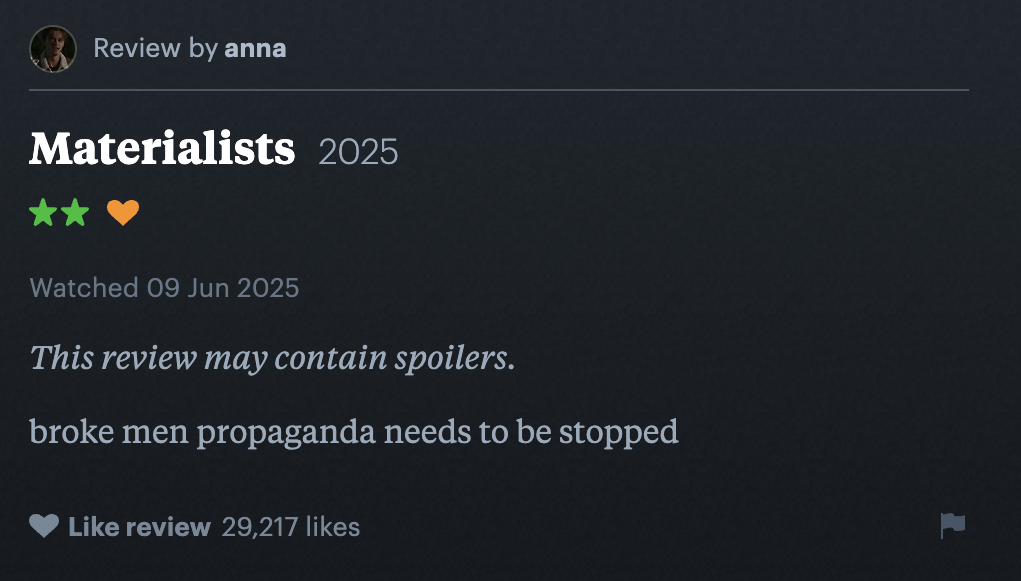

Spoiler alert: Lucy eventually ends up going back to John – a decision many audiences were unsatisfied with, evident from the cavalier Letterboxd reviews calling the film “broke men propaganda”. But this “broke men propaganda” is exactly Song’s purpose for this film. She wants us to challenge our preconceived notions that we have been conditioned to believe in from trying to survive in a capitalistic society, which in this case, is that a richer man is a better subject of desire than one who isn’t.

The top review of Materialists on Letterboxd calls the movie “broke men propaganda”. While obviously a joke, Celine Song was not impressed by the connotations of it, as she explains here.

For most of the film, Lucy and Harry’s relationship seems to go well, and they never seem to run into conflict with each other. Song knows that the audience will most likely root for her to choose Harry (and she was right) – but she does a bait-and-switch when Lucy ends up breaking up with him upon realising that he wanted to propose to her. Instead, she seems to prefer the more chaotic and less-than-ideal companionship with John instead. In contrasting the two relationships and showing who Lucy choses, Song acknowledges that romance can be engineered if both parties really try to make it work – but the je ne sais quoi of a relationship with the right partner can never be triumphed.

Using Lucy’s middle-man status as a bridge, Song explores both ends of New York’s socioeconomic spectrum, questioning her curiosities about modern urban romance. While she satirises capitalism and superficiality in the film, she stops short from completely denouncing it, showing an awareness of the reality of finding love in a capitalist world. Lucy’s relationship with Harry proves that financial stability undeniably makes relationships an easier pursuit; meanwhile, her ending up with John seems to subvert the hierarchy of needs, proving that there might be more comfort in love and familiarity instead. While money is an extrinsic matter that should not affect the intrinsic value of love, its power and impact forces us to confront it in everything we do, not excluding the act of loving itself.

It makes sense that in a society where love-triangle romance flicks like Challengers and The Summer I Turned Pretty reign the cultural landscape, that audiences might perceive this film from a typical rom-com perspective. But Song’s rejection of the “better” pick is exactly the antithesis of the cultural zeitgeist, the same way Materialists is essentially a rejection of the mainstream consumerist ideals that permeates our culture.