Lesbian Fight Club? Well, It’s Complicated

Guest writer Khushi Pai dissects the lesbian film that quickly garnered a cult following Bottoms (2023), and what makes it more than just a casual high school rom-com.

In critiquing a new film, one is faced with a choice: to analyse its "objective" artistic merits—to ponder what elements will endure decades from now—or to examine it as a cultural artefact, a mirror reflecting the anxieties and aspirations of the time in which it was made. Bottoms (2023) demands both approaches. It is, on the one hand, a riotous high school comedy with satirical flair that seems destined for cult status much like its predecessors, Superbad (2007) and Booksmart (2019). On the other, it is a striking contemporary work that illuminates the fissures in our collective understanding of identity, power, and belonging. Beneath its anarchic veneer lies a film that is as sharp in its critique as it is messy in its execution, making it both exhilarating and uneasy to engage with.

The film follows Josie (Ayo Edebiri) and PJ (Rachel Sennott), two misfit lesbians who launch a self-defence club under false pretences: not to empower their peers but to get closer to their respective crushes. This subversive conceit—part satire, part farce—morphs into a chaotic exploration of high school social dynamics, sexual politics, and, ultimately, the limits of societal acceptance.

A Post-Gay Universe?

The concept of "post-gay" ideology, which emerged in the late 1990s, heralded a shift in queer representation within Western media. It marked the integration of LGBTQIA+ identities into mainstream narratives, often tailored to a predominantly heterosexual gaze. Respectability, individuality, and adherence to heteronormative gender roles became the hallmarks of this new visibility. Bottoms toys with these notions, positing a world where queerness is unremarkable, accepted without question. Yet, the film also deconstructs this premise, exposing the enduring undercurrents of prejudice and the shifting parameters of marginalisation.

In the ostensibly inclusive high school setting of Bottoms, Josie and PJ are not ostracised for their sexual orientation but for their perceived lack of desirability and talent. Rhodes, a former babysitter and a kind of spectral mentor figure to them, encapsulates this shift when she poignantly remarks, “back when I was in high school, and people discovered I was gay, nobody wished to be my friend. Back then, it was even more challenging because they despised you solely for being gay, not for being gay and untalented.” The line is both biting and self-aware, a reminder of how far we have come and how far we have yet to go. This world, however, is no utopia. When Josie confronts Jeff (Nicholas Galitzine), the archetypal golden boy, to defend her crush Isabel (Havana Rose Liu), she is met with homophobic slurs and a community that swiftly brands her and PJ as "horny freaks," contrasting sharply with the tacit approval of Jeff's behaviour, despite his infidelity and involvement with older women. These moments reveal the fragility of the post-gay fantasy, where acceptance is conditional, precarious, and often superficial.

The Politics of Popularity and Queer Representation

High school comedies have long served as microcosms for societal hierarchies, and Bottoms is no exception. Here, the politics of popularity are inextricably tied to Whiteness, attractiveness, and conformity. Jeff, the unexceptional yet idolised quarterback, epitomises these values. His mediocrity is not a barrier to adulation; rather, it is his privilege. By contrast, Josie and PJ must navigate a labyrinth of scrutiny and double standards. Their queerness is tolerated, but only when it conforms to prescribed boundaries of behaviour and presentation.

The self-defence club—a ruse designed to seduce their crushes—becomes a vehicle for both empowerment and satire. On the surface, the club lampoons the commodification of feminism and the performative nature of allyship. However, Bottoms earns my commendation for admirably refraining from glorifying or justifying the morally dubious actions of its characters, presenting them as flawed and realistic individuals rather than idealised figures. This departure from the trend of sanitising portrayals in contemporary media embodies the subversive ethos of Generation Z, rejecting the puritanical norms that once dominated and instead embracing a more rebellious sensibility, reminiscent of the homage it pays to David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999).

Nonetheless, the central premise also risks perpetuating the stereotype of conniving lesbians solely driven by sexual conquest. The climactic kiss between PJ and her love interest, framed as both transgressive and voyeuristic, underscores this tension. While the scene appears to be a self-aware critique of fetishisation, its execution complicates this reading. The kiss becomes a spectacle, distracting an entire football game and reducing their intimacy to entertainment for the onlooking crowd who liken the moment to gay pornography. For queer audiences, this might register as a knowing satire of how lesbian desire is commodified, but for straight audiences, it risks landing as just another rehashing of the very trope it seeks to critique. This ambiguity is heightened by Brittany (Kaia Gerber), whose delivery flattens the intended irony, making the moment feel more like it’s punching down or sideways rather than effectively subverting the cliché. So, while Bottoms engages with the complexities of queer representation, it occasionally stumbles, risking a punchline that lands uncomfortably close to the stereotypes it seeks to subvert.

Race, Gender, and the Hierarchy of Privilege

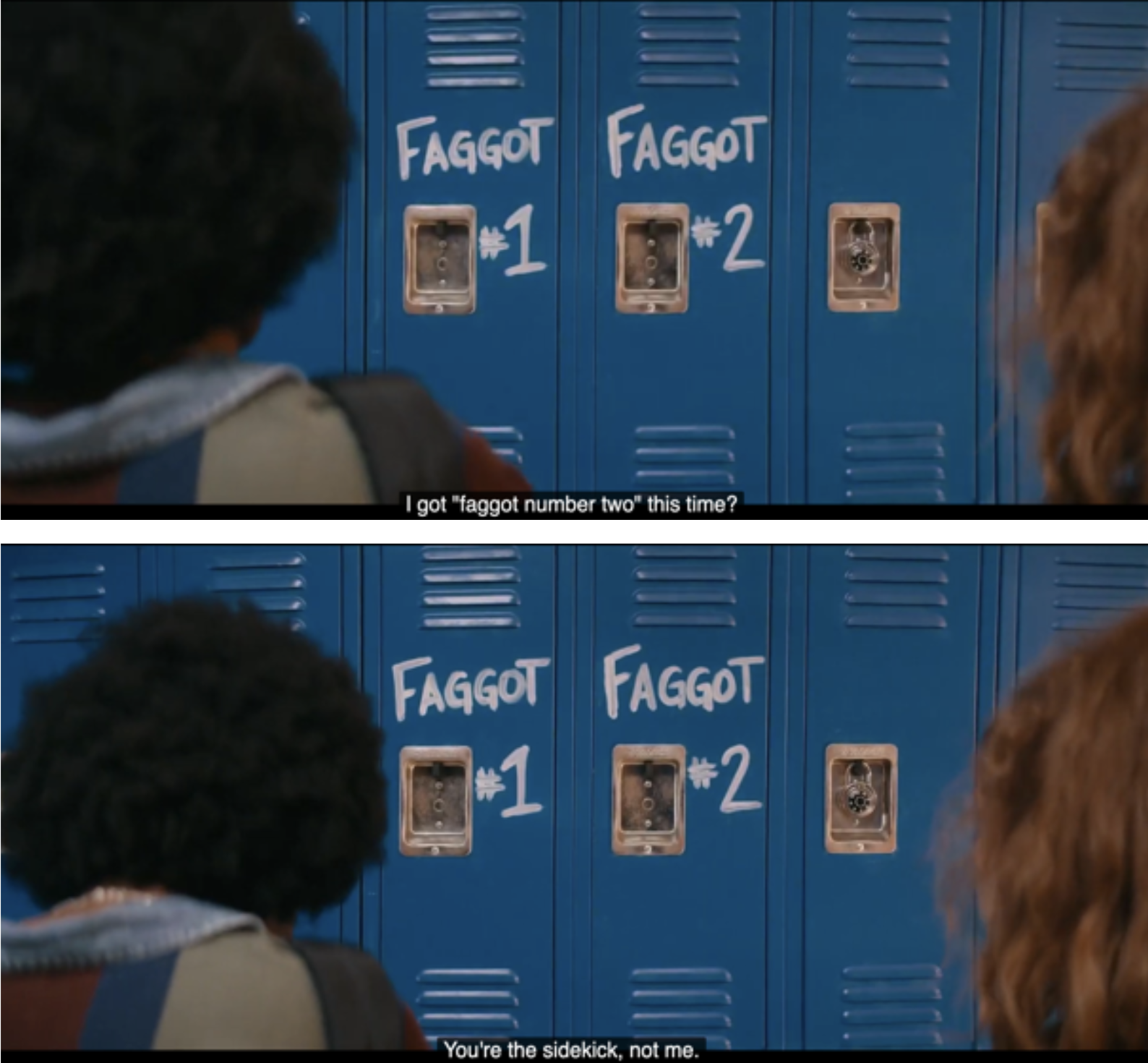

Bottoms is most incisive, however, in its exploration of intersectionality and how culture is inscribed onto the body. Josie and PJ, though united by their queerness, occupy vastly different positions within their social ecosystem. Notably, it is PJ's feminine appearance, coupled with her Whiteness, that affords her privilege, leading her to assert her perceived superiority. This is evidenced by her objection to being labelled "F-slur #2" and her expectation of being the leader rather than the sidekick. Even when faced with derogatory remarks, PJ’s White privilege and solipsism blind her to the reality of her situation, reinforcing her belief in her inherent superiority and mastery over the environment.

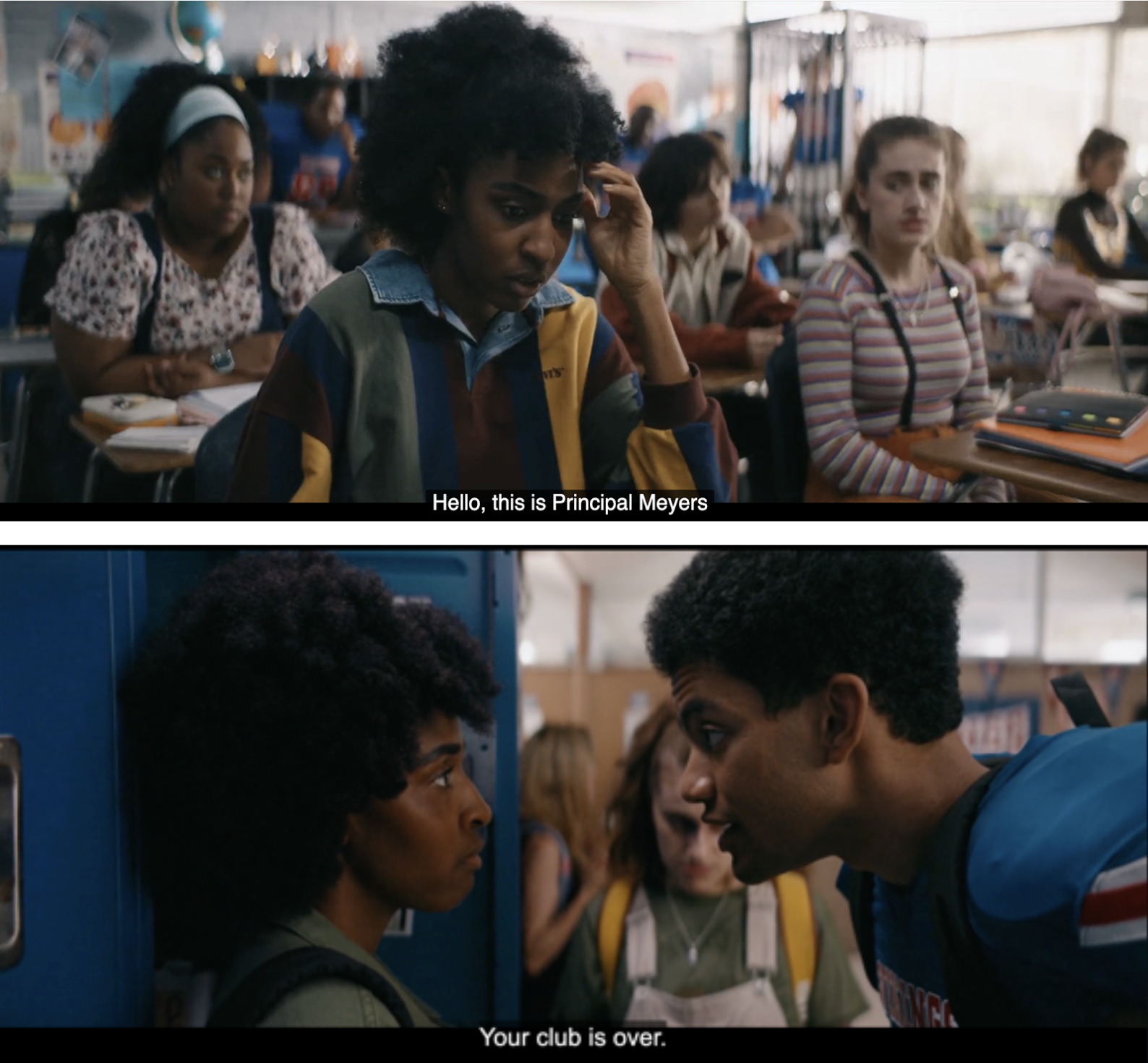

Josie, by contrast, is both Black and butch, and these intersecting identities render her more vulnerable to the scrutiny and aggression of their peers. This disparity is starkly illustrated after a confrontation in the school parking lot. Though both Josie and PJ save Isabel from Jeff’s toxic grip, it is Josie alone who receives a death threat, likely a consequence of how her racialised masculinity positions her as both, a target and perceived threat. The camera focuses on a distressed Josie, heightening the sense of anxiety and scrutiny that uniquely burdens her as a person of colour. This visual choice subtly absolves PJ of any blame, directing the audience’s empathy and tension toward Josie. While she does not fit conventional definitions/understandings of gender, her butch lesbian presentation is filtered through the lens of Black masculinity, shaping how she is viewed and policed. These moments expose the uneven burdens placed upon marginalised identities, even within a narrative that purports to dismantle them.

A more complex observation emerges in the characterisation of Tim (Miles Fowler), a seemingly secondary figure, yet one whose presence speaks volumes about masculinity, particularly Black masculinity. Defying the archetype of the monitored Black man, Tim instead wields the gaze, assuming the role of surveillant and enforcer. Yet, his authority is not merely a subversion of racist surveillance tropes; it is also a gendered one. His maleness and presumed straightness grant him a position of power over Josie, reinforcing the deeply embedded structures that dictate who observes and is observed. Their shared Blackness does not translate into solidarity; instead, it becomes the site of further stratification, where masculinity is weaponised against Black queerness.

This dynamic creates a nuanced interplay of essentialism: Josie’s recurrent entanglements with Tim evoke connotations of the criminalised Black lesbian stereotype, while Tim, in sidestepping conventional tropes, does not escape their gravitational pull, but rather orbits into another fraught category— the observer. Yet, this shift is no liberation. If anything, it is an entrenchment in a different but equally insidious hierarchy. Tim’s clandestine observation, voyeurism, and investigative prowess contribute to his ultimate vilification, perpetuating pernicious narratives of the problematic Black male figure.

At the same time, his position speaks to a well-documented pattern: marginalised men, even while subject to oppression, often replicate patriarchal power structures against women within the same margins. Thus, his role in the film is not merely one of surveillance, but of complicity in a broader system that disciplines and polices Black queerness. His character lays bare the indelible cultural scripts etched onto Black bodies, even in a satirical framework.

Conversely, Jeff is idolised and framed comedically as a Casanova. His machismo physique, prominently featured on school posters with his football jersey (#1), serves as a persistent visual motif of the elevated status White men enjoy within both, the high school microcosm and broader societal dynamics. Jeff embodies the archetype of the successful White male who rises to prominence effortlessly, while his teammates, notably people of colour, are relegated to supporting roles; his privilege allows him to coast on his image, his moral failings deflected or ignored.

And ironically, it is Tim, Jeff’s sidekick, wearing the #2 jersey, who drives much of the narrative forward. Tim’s unwavering subservience to Jeff is exemplified by his meticulous monitoring of Jeff’s pineapple allergy— an absurd yet pointed symbol of Tim’s relegation to a position of servitude. This dynamic, despite emasculating Jeff to some extent, also reinforces harmful stereotypes of the scheming Black male. The #2 jersey’s symbolism further highlights Tim’s subordinate role, suggesting that, despite his intelligence and vigilance, he remains confined to Jeff’s shadow, never allowed to transcend his secondary status.

Tim’s narrative arc ultimately reflects how Black masculinity is constrained and caricatured in ways that serve both, plot and comedic relief. Even in his resourcefulness, Tim cannot escape the larger cultural narratives that box him in as both, indispensable and disposable: powerful enough to aid the story, but never to dominate it. His interactions with Jeff and Josie alike expose how the inscription of cultural expectations onto bodies, whether through Tim’s role as an enforcer or Josie’s butch presentation, shapes the film’s broader commentary on privilege and intersectionality.

Beyond Post-Gay?

In essence, Bottoms serves as a compelling representation, yet it grapples with the very issues it seeks to portray. Set in a purportedly post-gay society, the film subtly reveals the unfulfilled promise of gay rights. Its depiction of queerness and race is a complex tapestry— at times authentic and normalised, and at others marred by the perpetuation of negative stereotypes, serving as an all-too-familiar reminder of reality. Perhaps this messiness is precisely the point. The refusal of Bottoms to conform to tidy narratives of queer respectability is an act of resistance in itself. By celebrating its characters in all their flawed, chaotic humanity, the film resists the pressure to sanitise queerness for mainstream consumption, and revels in the contradictions of its world, inviting viewers to grapple with the complexities of representation rather than offering easy answers.

Ultimately, there is undeniable value in what Bottoms offers to the queer narrative. It sparks necessary conversations, pushes boundaries, and dares to be imperfect— a reflection of the struggles inherent in representation itself. I first caught the film with a good friend, and its raunchy humour translated brilliantly for the both of us, evoking laughter that felt cathartic and genuine. As I reflect on its brilliance, I know I’ll always remember Bottoms fondly: for its sharp wit, biting critiques, and unapologetic messiness. If anything, it reminds us why pushing the queer discourse forward, even imperfectly, is not just worthwhile— it’s essential.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021