To Hold Film in Your Hands: From the Notebook Of…; We Are Toast

Editor-in-chief Goh Cheng Hao dwells on the physicality of film and the intimacy of filmmaking in this piece examining Robert Beaver’s From the Notebook Of….(1971/1988) and filmmaker-artist duo Mark Chua and Lam Li Shuen’s expanded cinema performance We Are Toast. In an age where our interactions with film are so disembodied, what does it mean to hold film in your hands?

The other night, I finally watched Robert Beavers’s experimental From the Notebook Of… (1971/1998), long overdue and recommended by a dear friend. A film about filmmaking itself, it loosely interprets essayist Paul Valéry’s writing on Leonardo da Vinci’s artmaking process, walking the viewer through Beavers’s own investigations with form.

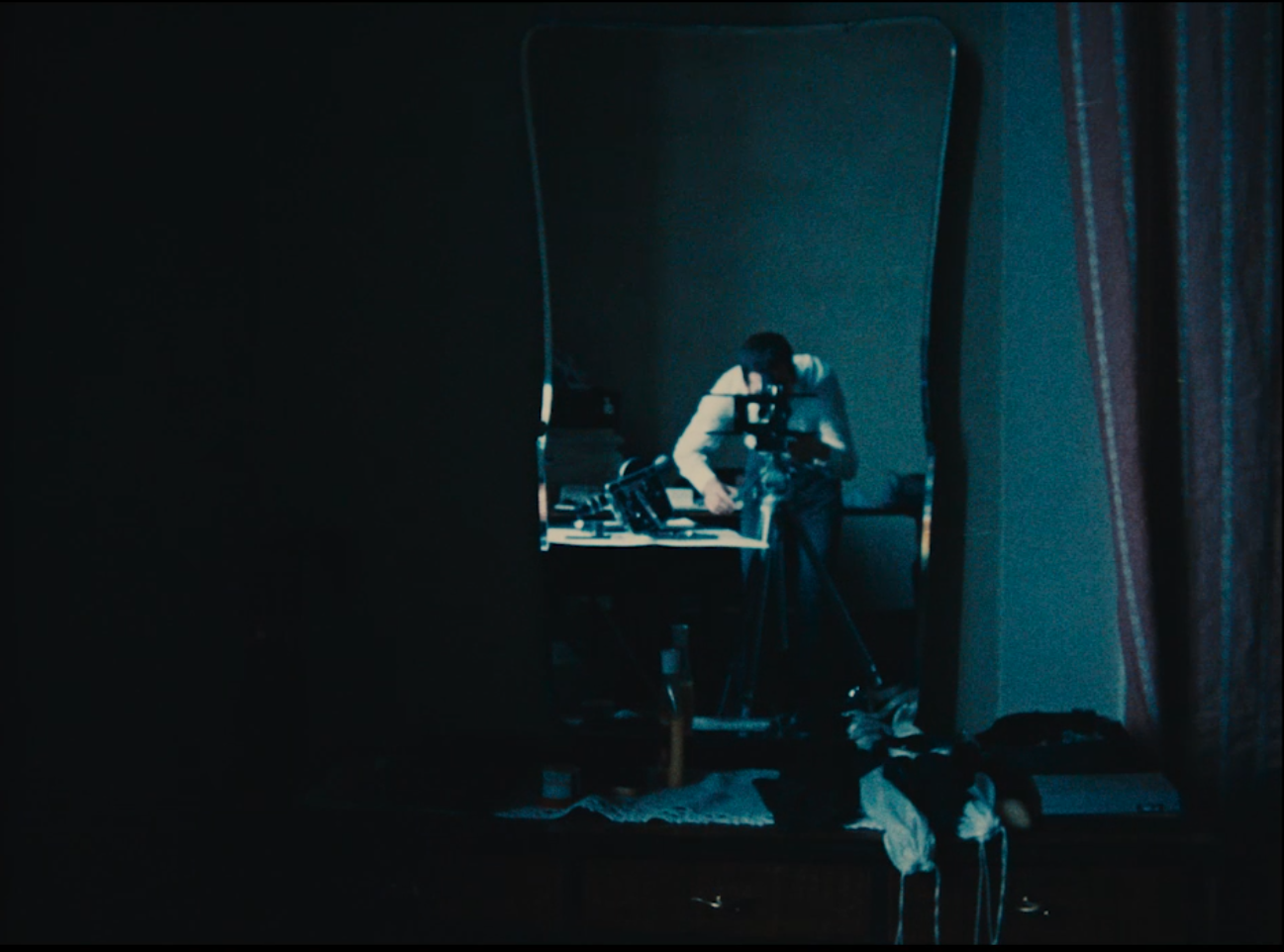

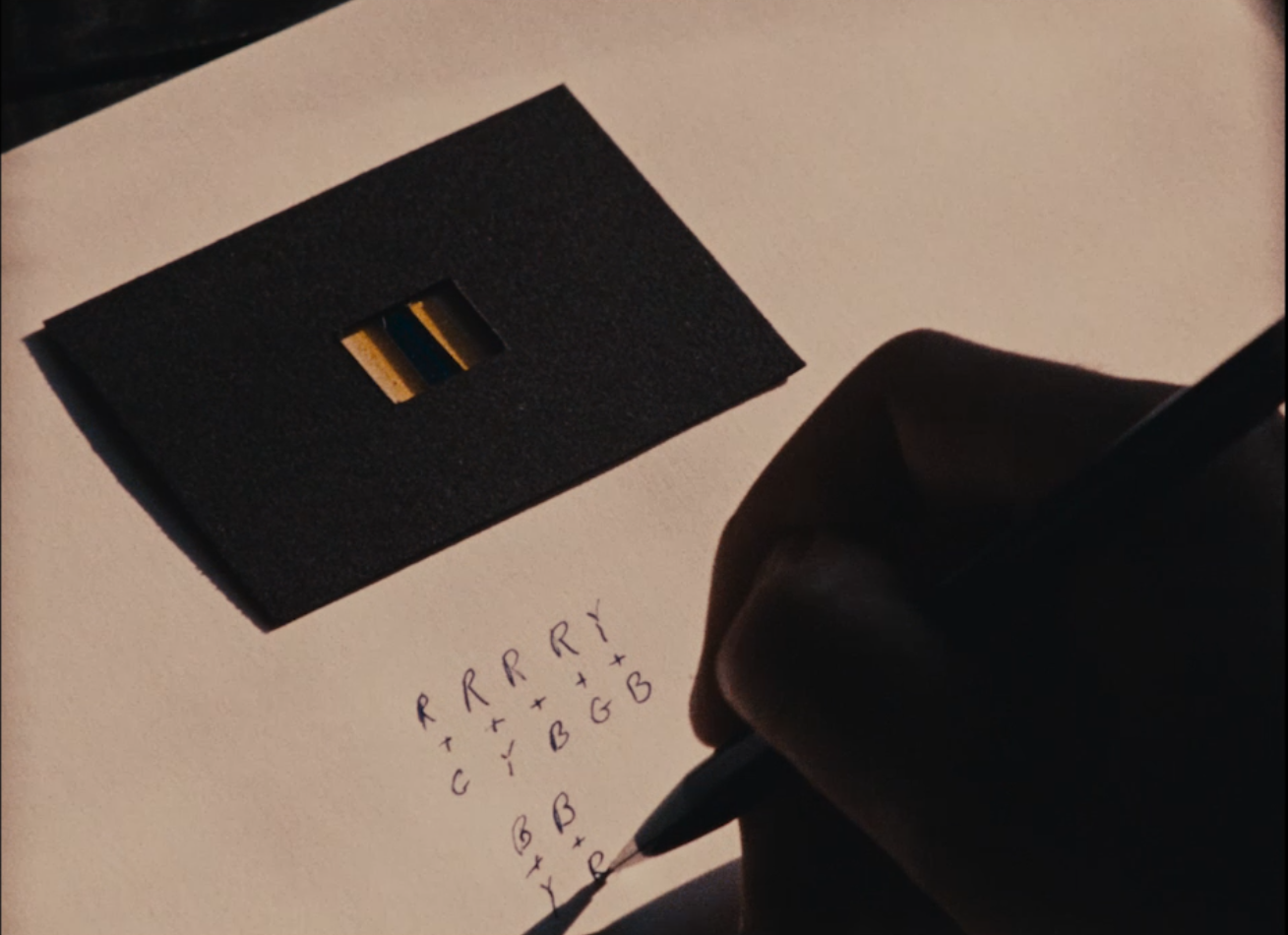

The film surveys his handwritten notes and experiments, cut with a medley of sights: birdflight, the male form, specks of light through leaves, vignettes of the city and its people. Beavers methodically documents his instructions and diagrams: “Close the window shutter to a crack; film my reflection in the mirror as my head moves in front of the narrow light”, the action is then demonstrated, cause and effect, trial and error.

There is no final product or film, however, for this is not a making-of. Beavers is uninterested in creating a coherent narrative for consumption.

Filmmaking for Beavers, it seems, is about play. It is about the subtle joys of interfacing with a medium, tinkering with its matter, toying with its shape. Of pushing its limits of representation. Much like Stan Brakhage’s formal experiments of inscribing or hand-painting onto a film’s surface, it is about the responsiveness of film. As someone who used to – and aspires to – do art, there is an indescribable childlike wonder to creation. It is about translation: of emotion, or simply just fancy, from an input to an output. It is about being translated.

Filmmaking is like a language – not that art isn’t often attributed to a visual language already – but one that is strangely hard to place. It is tactile like sculpture, moulding to your touch. But it is flat like photography, bounded like painting’s frame. And it is yet also hazy and intangible in its projection of light. It is all these and more. To shoot film feels like babbling with a new tongue, inventing new words, vocabularies. And maybe it is cathartic, helping metabolise something within and using images to convey the unspeakable where words cannot.

And yet, film similarly has its own gaps. Its photochemical processes are obscure (are we entirely sure what happens within that black box?), and it feels like a part of it always seems to stubbornly resist our attempts to control it, much like the slipperiness of language. And perhaps the filmmaker is also something of a poet – there is kinship in the rhythmic motions in From the Notebook Of… with metres of sonnets. The haphazard cuts fragment the film like enjambment in a verse.

If we are made of language – that our perception of self is mediated through the language(s) we speak – a new one makes us reconsider ourselves and our cognition. It becomes less about how we see with a camera, but how its invention has changed the way we see, how we interact with images.

Oftentimes, we only ever see a film’s final, fully-fleshed out form in spite of all that goes into creating it. To me, the image is a despot. It is immediate, tyrannical, and commands our total attention. But From the Notebook Of… averts its gaze from the spectacle of the image: it looks at filmmaking’s unseen labours. Critic René Micha wrote of how Beavers’s films are “anti-films…[destroying] the image of the cinema as we know it”. Beavers explodes the frame, letting us see instead the machinations of film that enliven its images.

Wielding a 16mm film camera, he plays with projections on glass, shoots through coloured filters and cut-outs, adjusts focal lengths, modifies exposure levels. A litany of repeated actions ad nauseum.

As much as film is play, it is also work, and undeniably it is work for the audience as well – we are likewise subjected to the monotony of these experiments. Filmmaking isn't glamorous, but neither is it necessarily tedious. There is something almost trancelike and ritualistic about From the Notebook Of… for both parties. Filmmaking is endurance, it seems to say.

Art historian Giorgio Vasari remarked in his seminal The Lives of the Artists – a familiar to any art history major – on how da Vinci would return caged birds to nature. Beavers restages this in the first few minutes of From the Notebook Of…. In an interview, he’d paralleled the flapping of the birds’ wings to the opening of shutters in his room in Florence.

From the Notebook Of…is then also preoccupied with motion. Beavers writes: “Film is not an illusion of movement, it is movement.”. The former: a window is swung open and closed, hinges well-due for an oiling scrape and turn, a matte stuck on the lens flips left to right. But we also then see the moving parts of the camera itself – the latter – the camera swivels, filmstock runs through spokes, amidst the metallic whirr of rotors, shutters click open and closed. It’s easy to forget that movement is such a crucial element to make and project film, when we are so distanced from its making.

But besides the movement of parts, it is also about the movement of hands, the people and their bodies that work to animate the film. Photographers and painters often produce self-portraits, but filmmakers are so often effaced from their own projects. From the Notebook Of…, however, visibly displays their hand in its creation.

We see Beavers through reflections on glass, we hear his pencil scratches on paper. The camera pans from left to right; a sliver of his face pokes out in the periphery, like a pesky thumb on the margins of one’s pictures but that reminds you gently of its photographer. Filmmaking is intimately intertwined with its creator, and bodily-y so. Art is vulnerable and tender and personal. There’s something nice, for a lack of better words, to put a face to its maker.

If anything, From the Notebook Of… reminds us of the physicality of film – its relation to physical work, physical motion, to real people and bodies and environments. In our digital age, in the nebulous (and tenuous) spaces of online streaming sites, film is weightless, frictionless, and flattened, a ghostly clump of pixels on a screen. But film is so inherently material and worldly: each second of film comprises twenty-four frames, nearly half a meter of polyester, and fifteen minutes weighs almost two kilograms (for 35mm film at 24 FPS, at least). It’s a funny thought that time and images can weigh so much, and take up so much space.

What does it mean to hold film in your hands? To thumb the sprockets that line its edges, to have its slick leaders slip out of your grasp, to hold its heft and sense its coils, tensed like a python. To have your fingers stained by the dirt and grease from the projector. To splice through the surprisingly firm plastic, or to feel its softness from deterioration.

And its smell? The sharp whiff of acetate and vinegar that makes you sneeze. Even CDs and DVDs have a smell of polycarbonate and a sense of fragility in your hands (so as to not scratch it). And to hear film? Not the sound of its movie, but the steady beat of its projector, the static from scuffs on sound-on-film. Even images are lost in the transfer from film to digital. Digital noise reduction removes grain, and we also leave behind cue marks (AKA cigarette burns, the ones Tyler Durden mentions in Fincher’s Fight Club) that would have prompted projectionists to switch out the film (interpositives were used for digitisation instead of release prints)

All these senses are lost to the unfeeling-ness of the digital and virtual realms.

In Fight Club (1999), Tyler Durden breaks the fourth wall by pointing at where a cue mark would be on a film reel.

There’s something incredibly intimate about physical media that I love so, so much. Elsewhere, I’ve waxed poetic about this for forever, but it bears repeating again and again. Its celluloid surface chronicles the marks of the hands it’s passed through, archives the imprints (and fingerprints) of the people it’s met, the distance it’s travelled – again, film and its movement; around the world! Even when a film degrades from its numerous screenings, it hints at its popularity, expands into the world around it. The marks on film reek of its past, reminding us that even objects have a life of their own. And how films used to travel! Dispensed from a factory to a filmmaker, to a darkroom to be processed, sent back, duplicated into release prints and distributed. There is a vast genealogy of a film and its interpersonal relationships that can be gleaned from simply reading the faded stickers on its can, or by its handwritten labels.

In a chapter from his book Curating the Moving Image, Mark Nash describes the experience of viewing film as “one of registering process”, but also one that inherently involves human contact – “a projectionist to whom one can complain if the film is out of focus or if the reels have been projected in the wrong order”; the secretive room that you can trace to the aperture of the theatre’s back wall, inaccessible except by its handler. There still exists projectionist rooms, but they project digital DCPs – what is there left to imprint upon?

It’s a shame that films have become a digital spectre of its past, too pristine, too ahistorical, too inhuman. Films now exist in every crevice on the web, and yet belong nowhere.

On Sunday night, filmmaker-artist duo Mark Chua and Lam Li Shuen presented their expanded cinema performance We Are Toast live in the courtyard of the National Gallery. Using three 16mm film projectors, gutted to accommodate improvised looping mechanisms, they projected scenes onto suspended tarps. Ambient drones turned to frenetic, pulsating beats with muttered voiceovers.

There’s so much that can be said of its multilayered (haha) performance that made me excited for local art like never before. Kaya toast, well-agreed to be emblematic of a national breakfast – and by extension a national identity – is deconstructed. The duo slathered raw egg and kaya onto the reels, toast is forcibly smushed onto the lens of the projector: these elements of nationalism smother and clog the film reels, which gesture to repeated, hackneyed narratives. Quite aptly then, one of the projectors ends up breaking down. Their clever engagement with tactics of resistance affords a whole other essay – but I couldn’t help but compare the performance’s affinities to Beavers's film.

Again, film is about play and experimentation, but dialled up to eleven. The duo incorporates foodstuff and organic material – pandan extract, instant coffee, coconut milk, and mould – into the developing process. There’s this mad-scientist-esque kind of absurdity about it that thrills to witness. Mould seems to bloom on the surface of the film, the projection dulls when kaya is smeared on it. And what happens when you introduce the uncertainty and chance of living organisms into an otherwise inert medium?

But most of all, the performance encapsulated what artistic possibilities (and even so simply as experiences) we lose with our blind reverence to the digital. To see working film projectors in this age is already a novelty. But it is something special to have the ability to come into such close contact with film – they’d worn the loops of film around their necks – but also to handle and to see it morph and shift under your hands. And to film’s bodily aspects, they’d incorporated all the senses – the sweet smell of pandan, the speed of the projectors were programmed to match the tempo of the music, in the background the projectors whirred noisily, the stickiness of fingers.

The performance culminated with a nod to its title. Both artists laid atop one another, coated in kaya, a pat of butter and knot of filmstock sandwiched between them. Their bodies became intertwined with film, much like film is also entangled with the body. In their act, they seemed to defiantly answer – and so fittingly, given the history of films banned and rendered homeless in Singapore; the vanishing of spaces for art and cinema – this is what it’s like to hold film.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021