Views All Around: A Review of the 36th SGIFF’s Singapore Panorama

Staff Writer Yu Ke Dong surveys all four Singapore Panorama Shorts Programmes at the 36th SGIFF: with his finger on the pulse of contemporary filmmaking, what’s the prognosis for local programming and cinema?

To watch a short film is to catch a glimpse of something rare and remarkable. Armed with little more than a shoestring budget and borrowed equipment, the filmmaker sets out over the course of one or two nights–sometimes just a few hours–to create something unique, oftentimes telling a story no one has ever heard of. On occasion, the product of their effort goes on to great acclaim at film festivals, laying the groundwork for a potential feature somewhere down the road. For most shorts, however, they often languish in obscurity, a remnant of sweaty nights toiling alongside a ragtag gang of friends, trying to capture that elusive magic of independent cinema.

It goes without saying, then, that it is now more important than ever to watch short films. Short film programmes are often not taken seriously by mainstream audiences, perceived as being shorter and therefore less worthwhile in comparison to full-length features. Yet, these programmes are almost always meticulously curated and intentionally sourced, each selected short film entering into productive conversation with each other. Collectively, they speak to the myriad concerns and methodologies of independent filmmakers across cultures and geographies. Like a canary in a coal mine, these programmes indicate to us if the imaginations of young filmmakers are flourishing, or being slowly suffocated by an increasingly uninterested audience.

Showcased at the 2025 Singapore International Film Festival, Singapore Panorama’s Shorts Programmes provided a sweeping survey of local short films over the last year. Curated by film programmer Vess Chua, this year’s short film programme was organised across four distinct themes: they looked at motifs of the home, the margins, the absurd, and the supernatural. If short films are to be the barometer of the local filmmaking scene, what’s the prognosis this year?

Optimistic, as it turns out. While some shorts were perhaps left somewhat wanting, there were many more provocative presentations that suggest that local filmmakers are actively expanding the possibilities of their craft. This year’s edition featured several familiar faces–the likes of Nelson Yeo, Seth Cheong, and Kew Lin being well-known figures–but also introduced us to newcomers, first-time directors and multidisciplinarians whose early projects have already broken into public discourse. Having been lucky enough to catch all four of the short film programmes, I’m here to offer my (unsolicited) thoughts and opinions.

Before mentioning the highlights, it is perhaps worthy to briefly take note of the few shorts which, unfortunately, did not “slay” at this year’s short film selection. Of them all, Cendol by first-time scriptwriter and director Qi Yuwu is markedly disappointing. Given that the director has been a mainstay of Mediacorp dramas for several decades, audiences certainly came expecting mature, sophisticated work. However, it seems as though Qi’s tenure as a Channel 8 darling has proven to be more of an obstacle than an asset in his directorial debut. Cendol–a drama surrounding a middle-aged interior designer, her mother, and her ex-boyfriend–comes across as saccharine, shallow, and unimaginative. Saturated with slow-motion flashbacks of her zaddy ex (dead wife montage, much?) and overly elaborate Chinese dialogue, the film carries much of the trademark aesthetics of a soapy Channel 8 melodrama, but with none of the emotional stakes. Ruminating on Singapore’s local heritage, the film fails to come across as authentic or grounded, with the film’s main character rarely venturing out of her pristine upper-class enclave. Even cendol, a dish which everyone knows is best enjoyed mid-afternoon in a raucous hawker center, is inexplicably consumed by the protagonist in her comfortable, IKEA-showroom-esque flat. It raises so many questions: how did her mum manage to tabao the cendol back without it melting; is she hiding an ice grater in her kitchen? Regardless of its shortcomings and logitstical plotholes, this is still, after all, Qi’s first film, and we might hope that his subsequent projects would reveal a more realistic representation of our society: less polished, and grittier.

Another unfortunate miss is Seth Cheong’s Dogma 65 (Director’s Cut). Depicting two amateur filmmakers participating in a 48-hour short film challenge, the resulting short film pays homage to the struggles of two filmmakers trying to make a movie. The short ostensibly champions the importance of creation, the need to make art regardless of its quality, seriousness, or content–this much is an undeniably important message. But what it fails to do is to deliver that message in a way that is convincing or accessible.

The film attempts a frank exploration of the behind-the-scenes processes of filmmaking, yet its realism is somewhat undercut by wooden acting and poor cinematography, revealing each scene to be awkwardly and unconvincingly staged. Unfortunately, the film also hinges too heavily on niche film references. Its title draws from the 1990s Danish film movement Dogme 95, and at one point, one character remarks to the other: “You’re such a von Trier”, namedropping the eponymous filmmaker Lars von Trier. The film relies far too often on similar witty, referential repartee, perhaps trying to evoke the pretentious film bro archetype. Yet, without any attempt made to sufficiently explain or contextualise these droll remarks—or indeed, be critically self-aware of its own pretentiousness—the film feels less about a well-intentioned introduction to foreign filmmaking philosophies and more of an exercise in ego stroking. The film’s tendency toward self-indulgence works against its own message, inadvertently suggesting that filmmaking is not about being a democratic and accessible art form, and more as a circle-jerk club of inside jokes and niche references. Of course, Dogma 65 works just fine as a satire piece for knowledgeable film geeks that calls out its own self-importance; but when programming for a public SGIFF audience, I would argue that the task at hand calls for a more accessible, less self-involved message. In all, though, it brings up the perennial question: what kind of audience should films be made for?

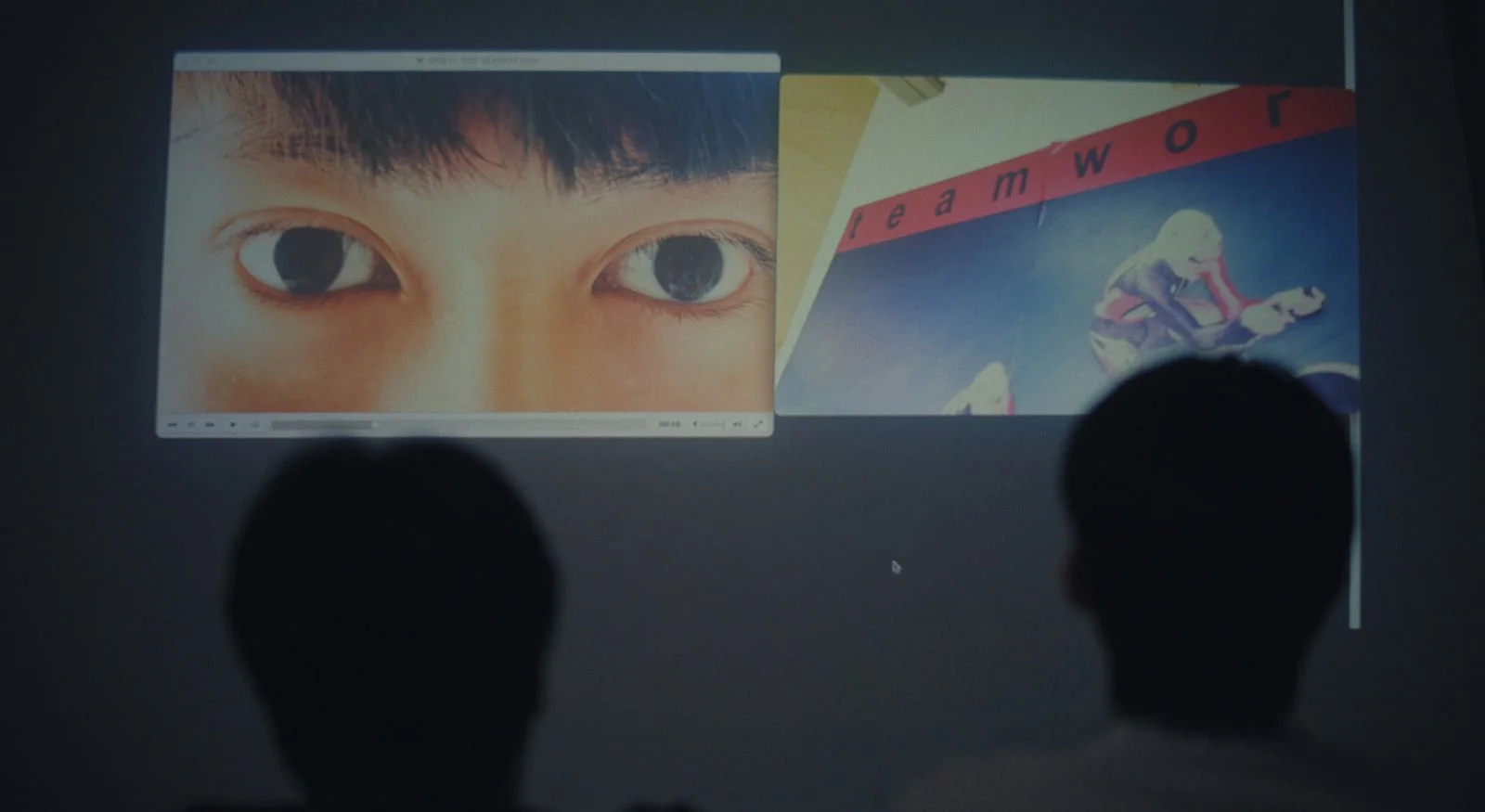

L to R: Jon Keng, When the Wind Blows, 2025; Pek Jia Hao & Ang Jia Jun, As if to Nothing, 2025. Images from SGIFF.

Now, onto the bangers of the programme–ones that managed to surprise and captivate, stealing the breaths of audiences present. Jon Keng’s When the Cold Wind Blows literally accomplishes this, attested to by audible gasps in the theatre. As a tale of two young troopers lost in Brunei’s wild forests, the resulting twenty-minute film is delightfully creepy and suspensefully supernatural. Cleverly harnessing the blind spots of the camera’s lens, Keng’s spectre lurks in the corners of our vision, springing out when we last expect it. When someone lets out a bloodcurdling scream in the middle of your short, you know you’ve succeeded as a filmmaker.

Along the same lines of the gothic-adjacent, Pek Jia Hao and Ang Jia Jun’s film As if to Nothing presents a meandering, brooding vision of a city in decay. Fleeing a local gang of thugs intent on buying out his property, the film’s unlikely hero–a weathered old man–shuffles silently through cluttered alleyways and dingy bars in search of his missing cat. As a mood piece, the filmmakers capture a unique, noirish aesthetic pieced together by scenes of surreal stillness and the liberal implementation of chiaroscuro, perfected by a slow, creepy bass guitar track–think somewhere in between slick Hong Kong neo-noir and Frank Miller’s Sin City movies. One particular scene at the halfway mark, shot in a sun-dappled sewer with veteran actor Lim Poh Huat, is unlike anything I have ever seen in local cinema. Equally beautiful and horrific, it sinks its teeth into your brain and latches on in the best possible way. The film marks the latest in Pek and Ang’s collaborative filmmaking practice, and I’m excited to see what’s next.

L to R: Yuga J Vardhan, The Last Rites, 2024; Tan Wei Ting, Withering Tree and Living Ashes, 2025. Images from SGIFF.

It wouldn’t be a Singaporean film festival without entries about family dramas; among the entries submitted, Yuga J Vardhan’s The Last Rites and Tan Wei Ting’s Withering Tree and Living Ashes are undeniably the most accomplished. Capturing the final weeks between a kindergarten teacher and her declining father, Tan’s short balances the melancholic lows of living with dementia with moments of unexpected, mundane happiness. The film shines particularly well in depicting the quiet intimacy between the daughter and her lighthearted domestic helper, Rani, with whom the family forms a close bond. Meanwhile, Vardhan’s The Last Rites is a masterfully written portrait of mourning. Adopted into an Indian family, the film’s Chinese protagonist overcomes his relatives’ objections and performs the (titular) last rites for his beloved late grandmother. The director treats issues of ethnicity and religion with subtlety, yet each frame hangs heavy with unspoken tension, every hidden glance and soft touch laden with meaning.

While this year’s short film selection featured several brooding family dramas, Christine Seow’s travel documentary Two Travelling Aunties went in a completely different direction, delighting audiences with its lighthearted yet moving depiction of both biological and found family. The short follows couple Norah and Susie as they travel across diverse continents in Latin America, aiming to visit 43 countries in 6 years. As a couple, their relationship is not officially recognised by Singapore’s legal system. Yet, the pair remain undeterred, deciding to abandon conventional life paths and embrace the happiness of travelling nomadically and being in each other’s presence. Capturing the pair’s candid conversations in between sun-drenched scenes of van-life bliss, Seow’s graduation film provides a grounded yet deeply inspiring exploration of Susie and Norah’s love for each other. Suffice to say that there were few dry eyes among the audience that day.

L to R: Bart Seng Wen Long, Emergencies, 2025. Nelson Yeo, Durian, Durian, 2025. Images from SGIFF.

There were also a few left-field, genre-defying entries that embody a thrillingly experimental approach to filmmaking, most notable being Nelson Yeo’s Durian, Durian and Bart Seng Wen Long’s Emergencies. The former is an absurdist tragicomedy featuring two ordinary people seeking suicide by lying at the bottom of a durian tree; shot on glittering Super-8, the film is interspersed with musical scenes of the two dancing to Fei Xian’s classic 1998 hit song 流连 (Liu Lian)–meaning “linger”, but often misconstrued by Singaporean audiences as its homonym, the Chinese characters for the king of fruits. Playing on this popular pun, Yeo’s whimsical film combines the kitsch of a KTV karaoke video with the deadpan humour of Beckett’s enduring play Waiting for Godot. Long’s Emergencies is even more daring–a collage of spliced scenes from propaganda films of rubber plantations in early 20th century Malaya, the filmmaker intertwines voices of the past with images of an anonymous figure reclining in a head-to-toe rubber gimp outfit, a continuation of the filmmaker’s work with marginal sexualities. What emerges is spellbinding, irreverent and mind-bending, a film that free-floats through past and present imaginaries of the 1948 Malayan Emergency, surveying global resource economies and political crises in a meditation of contemporary postcolonial legacies.

L to R: Izzy Osman, The Water is Blue in Tanjong Katong, 2025; Azina Binte Abdul Nizar, We Learn to Breathe in Distant Places, 2025; Ash Goh Hua, Full Month, 2025. Images from SGIFF.

This year’s short film offerings also featured contributions from a new cohort of rising filmmakers, whose works foreground exciting new possibilities as they continue to develop their practice. Among them is Izzy Osman, a young director whose accolades include a BFA in Film from Pratt Institute and a stint working for A24 in New York City. Returning to Singapore, Osman excavates cultural memory in her nostalgia-steeped debut, The Water is Blue in Tanjong Katong. Featuring conversations with local fans of the late great P. Ramlee, her light-hearted documentary takes an unexpected yet welcome turn for the speculative by projecting scenes from the auteur’s broad oeuvre onto various building facades, manifesting the collective desire to keep the past alive even as the nation barrels into the future.

Another emerging artist worth keeping an eye out for is Azina Binte Abdul Nizar, whose short film We Learn to Breathe in Distant Places explores the anxiety of a mother whose child inexplicably disappeared into the forest. Though her script falters at certain places, Azina’s film thrives in its dreamy, surreal forest scenes, beautifully shot in a way that is reminiscent of Apitchatpong Weerasakul. Using the mystical jungle as a site where the supernatural and the personal unfold and collide, Azina’s sophisticated storytelling weaves an intimate narrative of gender and freedom within the familiar confines of family.

Perhaps the most decorated of the rising filmmakers shown at SGIFF this year, Ash Goh Hua’s first narrative short Full Month had premiered at the prestigious Sundance Festival earlier this year, before making its Asian premiere at SGIFF. Following a queer artist who returns home from her life abroad to her conservative family, the film depicts subtle tensions through mundane gestures and near-unnoticeable moments–a smile tightening, or a hand withdrawn. Goh’s work is imbued with a certain emotional rawness that can only be found in the autobiographical, drawing from her own estranged relationship with her mother as well as her experiences moving to NYC after graduating in Singapore. Her previous film, The Feeling of Being Close to You, incorporated conversations between Goh and her mother over the phone as well as old recordings of the artist as a child, the latter recurring as a significant motif in Full Month. With the support of the prestigious 2025 Creative Capital Award, Goh is currently working on developing her short into a feature film, as well as some promising new projects.

On a final note: as much as it is important to give credit to the amazing films screened at SGIFF this year, it is equally important to talk about those that were unfortunately blocked from reaching audiences by the festival’s own host organisation. Several days before it was set to debut, Nurain Amin’s Proposals for the Interpretation of a Dream was refused classification by the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), with the claim that it “contains inaccuracies in its portrayal of Islam which are objectionable and misleading”. Singaporean filmmakers are, of course, no stranger to the interventions of the IMDA. Last year, Daniel Hui’s feature Small Hours of the Night, a scathing critique of the state’s legal systems, was ironically refused classification due to it being “potentially contrary to the law”. I find it very much futile to contest these rulings as unfair or unwarranted–it’s clear to see that local artists continue to exist in a landscape where censorship is routine, a hostile environment that ends up stifling the vitality of the arts scene even as the government purports to keep it alive.

Yet, I would argue that in banning this film, SGIFF audiences were deprived of the opportunity to watch something truly fascinating. Amin’s film is boldly experimental, a vibrant tapestry of live action footage blended with 2D and 3D animation. Centered around a Malay Muslim woman’s journey of self-discovery as a young student living abroad in France, the film is deeply personal, synthesising not only Quranic scripture but also European Occultism, notions of death and rebirth, and even appropriating Freudian psychoanalytic methodologies (as the title suggests). There is a striking scene where the protagonist, lost in the memories of an unknown other, sees herself hiding in a tree from a Japanese soldier standing down below. Gazing out of the eyes of the unknown hider, the audience hears her fearful breathing as the soldier locks eyes with her and waves, smiling. To foreign audiences, this may not mean much. For me, however, it immediately evokes my own grandfather’s harrowing stories of escaping Japanese troops during the Occupation of Singapore in 1942. While the story is starkly her own, its ability to resonate so intimately with me speaks to the filmmaker’s capacity to touch both the general and the particular.

Certainly, Amin’s film is not perfect–some of the green screen effects are a little uncanny, and some of the colouring remains unpolished. Nonetheless, as a radically unique piece of work, her film opens up a world of possibilities within the realm of experimental filmmaking, something that more local independent filmmakers could stand to learn from. As much as we lament the effects of IMDA’s censorship, however, it is also heartwarming to know that barring a film in Singapore often generates the opposite effect of what was intended. Much like Tan Pin Pin’s To Singapore With Love, the IMDA’s refusal to classify often draws the attention of critics and general audiences with something of a macabre curiosity, inevitably reigniting debate that recenters the important topic of creative liberty in Singapore. Censorship tends to breed a certain tenacity with filmmakers, those who are undaunted by forces greater than themselves, and will stop at nothing to convey their message one way or another. With any luck, we’ll be able to witness Amin’s work return to the silver screen some time in the near future.

Ultimately, this year’s selection of short films at SGIFF Panorama is certainly worthy of public attention. Though some films may not be as compelling as others–as I have occasionally pointed out through the course of this review–the beauty of the short film format lies in its potential as an experimental space, where mistakes can be comfortably made and techniques can be honed through experience. Nevertheless, it is truly a privilege to glimpse the remarkable diversity of creative voices, both emerging and established, at SGIFF this year; it really goes to show just how vital the local film scene continues to be, in spite of overt attempts to censor those that are deemed, supposedly, ‘objectionable’.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021.