Kollywood at a Crossroads

Staff Writer Mohamed Shafiullah examines what he terms as ‘get-hyped’ films in Kollywood, looking beyond the tropes that dominate these films and delving into its ties to the politics of the region–as well as the consequences of having Tamil cinema and Tamil politics so strongly intertwined.

Is Kollywood at a crossroads?

Kollywood refers to the Tamil film industry in the southern region of India. An industry that, more or less, has become a business primarily focused on churning out mainstream, tentpole, Tamil films that I’ve termed ‘get-hyped’ films. What is a ‘get-hyped’ Tamil film, you might ask? Oftentimes, they feature a famous actor–who almost always has godlike strength and stamina–wrestling his way through life without losing style and grandeur, defeating the bad guys with his multitude of skills, and essentially aura-farming from start to end. Oh, and in most cases, he gets the girl, who has fallen prey to his charms.

Famous Tamil actors often have nicknames, which are usually bestowed upon the actor by fans or industry leaders. Rajini is Thalaiva (Leader), Vijay is Thalapathy (Commander), Ajith is Thala (another version of Leader), and Kamal Hassan is Ulaga Nayagan (Universal Actor). Imagine if Leonardo Di Caprio was nicknamed the God-King of Acting. You get the idea.

Such films used to be a part of the industry, but now they seem to be the industry itself. If I delve into the origins of the ‘get hyped’ genre of Tamil films, we’ll simply be stuck here forever. The most important thing to note are the characteristics of these films–the lead is always a cultlike figure with charisma and physical prowess, every other character is mostly one-dimensional and exists simply to serve the lead, and the common people almost always identify the lead as a god-given savior of sorts. Indian audiences go to watch these films because of the respective actor that stars in it, and not necessarily for the storytelling. Once upon a time, even when making ‘get-hyped’ films, filmmakers still understood the need for a well-written, tight and polished story. The star power of their publicly adored lead was considered as a bonus, and not the point in and of itself. There was also space for films that featured lesser-known actors–ones that prioritized a tight narrative which reflected the sociocultural concerns of the day, and went beyond flashy sequence after flashy sequence with no depth.

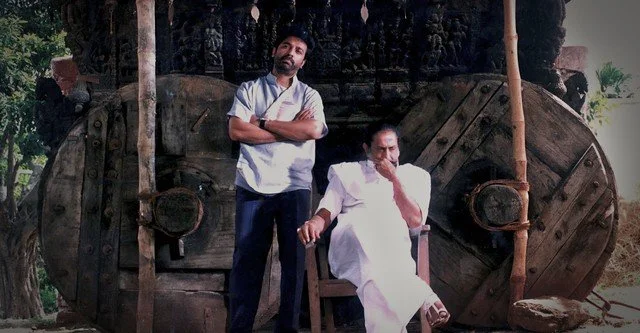

One such example of a mainstream Tamil film that paired a good story with a ‘get-hyped’ Tamil actor would be Thevar Magan (1992). It stars the Ulaga Nayagan, with a story that focuses on the conflict between the protagonist’s aspirations for progress and the traditional, violent expectations of his family and community in feudal Madurai. What makes it a good story? Kammal Hassan does not play Kammal Hassan as The Rock tends to play The Rock, but rather he is able to portray someone who is stuck between a life in the modern world and a life in a traditional village. The storyline has emotional depth to it; this is not about how Kammal Hassan as the lead is able to overcome insurmountable odds, but rather it is the opposite, of navigating the tensions that arise when dealing with communal friction and taking responsibility for one’s actions. Usually in the final scene, the villain is killed or destroyed and the hero is celebrated, and all is well in the end. In the final scene of Thevar Magan, however, after Kammal Hassan accidentally kills the villain, he refuses to allow his loyalists to take the blame. Instead, he surrenders himself to the police, leaving control of the village to his sister-in-law, re-negotiating the concepts of patriarchy and responsibility.

The industry has always managed to balance its ‘get-hyped’ (yet still narratively enriching) offerings with its more artistic and grounded fare. But this balancing act has since turned to dust, and Kollywood is now dominated by these ‘get-hyped’ films, which have become ‘superhyped’. Fast forward to this year, you have the Ulaga Nayagan starring in Thug Life (2025); the title itself indicates westernized ideals, and the story can only be described as a nonsensical gangster tale with countless hype moments that overshadow any form of good storytelling. A far cry from the previously mentioned Thevar Magan, Thug Life is a representation of how far the industry has fallen. A painfully cliche moment that occurs in Thug Life, which almost always occurs in this genre of films, can be seen in the very opening scene when Kammal Hassan asserts: “I, Rangaraya Sakthivel, was fated from birth to become a gunda, a thug, a yakuza.” The lead self-indulges, self-proclaims himself as a fighter, a warrior, a leader; this is the ‘Immortal Gangster’ trope we oftsee in Kollywood.

The most egregious example of the artistically disastrous turn the industry has taken has to be the latest outing of the ‘get-hyped’ genre, Coolie (2025). The film stars Superstar Rajinikanth–arguably the most popular Kollywood actor in the South Indian community, and the most recognizable Kollywood face for foreign audiences. It features the Indian coolie community, indentured laborers who have a place in a history filled with tragedy, pain, horror and abuse. Rather than addressing any worthwhile aspect of the life of the Indian coolie, the film instead acts as a model example of this devolution of Tamil cinema, with all the hallmarks of a ‘get-hyped’ Tamil film exaggerated to the greatest heights possible.

The coolies are stripped bare of life; they merely come on the screen to help the protagonist fight off the villain, and the film isn’t really about them despite the title. They are portrayed as thugs, gangsters, fighters, which is such a disservice to the community because it marginalizes the truth and fails to foreground that the coolies were victims of colonialism and capitalistic greed. We are shown not a humanistic portrayal of coolies but instead a sanitized, untruthful, dramatized version, puppets whose only purpose is to glorify the protagonist even further. In Coolie, the coolies are able to rebel against their oppressors in a macho, suave manner, fighting with style; does this not disregard the actual coolies who were unable to resist larger societal forces, the capitalists who got them hooked on opium and stuck on plantations? If we were to expand the argument a little, the failure to portray coolies truthfully means the colonialists who controlled these coolies are portrayed untruthfully; not as an institutional, state-level force to be reckoned with but rather as something that can be overcome locally and individually.

Can a rich, privileged actor like Rajinikanth do justice to the portrayal of a working-class character? Rajinikanth was a bus conductor before being launched into stardom; one cannot say he does not understand subalternity, but of course he is now far removed from where he was in terms of class and status. So where do we draw the line? Not only for Rajinikanth, but also for the other rich and privileged Tamil stars who portray working-class characters trying to navigate-working class problems, when does it become an issue of ethics? If the working-class folks who watch and adore these films do not have an issue with how they are represented, choosing to support the movies of such superstars, who am I to question the accuracy of these films? On the contrary, if indeed it is unethical and inaccurate for such megastars to portray working-class actors, we run into the problem of underrepresentation. If big-budget films no longer featured subaltern lived experiences for concerns over inauthenticity, who will tell these stories? Aren’t imperfect stories better than no stories? And we have not even considered the motives and biases of the other industry players involved, such as the producers, directors and financiers of these films. Questions seem to lead only to more questions.

When did Rajinikanth cease to play a character and start to merely play a grandiose version of himself? It is hard to say. The mythicization of Tamil megastars is not a linear process. It does not start and end with one film, a film that separates their acting careers into two distinct styles, the former where they portray characters and the latter where they portray a fictional version of themselves. It is an amalgamation of stylistic actions; Rajini turns his sunglasses in a particular way in this film, and he does the very same in the next film. Slowly but surely, the turn of the sunglasses is not the style of the character but now the style of Rajini. So what starts out as an in-character action, part of the diegetic space, is slowly removed from that space and instead represents Rajini the person himself, no longer just the character. These stylistic actions, collected across various films, when performed in a single film, tell you that you are not watching Rajini play someone, but Rajini playing Rajini.

Beyond the mischaracterization of the lived experiences of subaltern lives, such films have material consequences on our present. Tamil cinema and Tamil politics are strongly intertwined, many famous actors eventually going on to become politicians. Throughout Tamil politics, actors dominate ruling parties and ruling positions. For every Hollywood celebrity that receives backlash for expressing their political opinion, with the complaint that “who do these out-of-touch celebrities think they are, telling me how to vote?” there is a Tamil actor who enters Tamil politics without a second thought or much backlash.

Although much can be said about exactly why this phenomenon exists in Tamil politics, what is important to note is that recent Tamil cinematic offerings have only stimulated the actor-to-politician pipeline further. The cinematic extremity that is ‘get-hyped’ films build these Tamil actors into godlike and cultish figures, and when they enter politics, they secure significant political capital (such as votes) even though they might not have any political qualifications, simply because the audience has been trained to glorify these men. And what happens when the worst combination takes place, someone who lacks every political skill but possesses all the aura collected throughout their get-hyped films? A disaster waiting to happen, with real lives at stake, and Kollywood definitely must take the blame.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021.