Smiling Through It All: A Review of PlayTime (1967)

Staff Writer Kyle Ashley Pillai explores Jacques Tati’s arthouse classic PlayTime (1967), examining his visions of the future and how its celebration of the human spirit amidst modern chaos still resonates with contemporary urban life 50 years later. PlayTime was screened as part of the first half of ArtScience Cinema’s Visions of the Future programme.

If you’ve ever encountered a SingLit piece, chances are you’ve stumbled across one where the subject matter covers the superficial artifice of Singapore’s construction (think Boey Kim Cheng’s The Planners or Joanne Leow’s Seas Move Away). It is indeed a familiar notion in Singapore’s cultural discourse that the country is sterile and cultureless: pristine on the surface, hollow on the inside. But is that all there is to our modern society, or is there something more to behold about this little red dot as it marches on towards the future?

This tension sits at the heart of PlayTime, the fourth and most ambitious feature by French auteur Jacques Tati. Being the most expensive French production of its time, Tati largely funded the film from his own pocket and took out loans, a gamble that ultimately led to his bankruptcy. The hefty cost shows in the film’s production design. An entire city was created, nicknamed ‘Tativille’, filled with intricate labyrinths and high-rise architecture made to mimic the propensity of modernisation. Much like Singapore’s own urban logic, Tati’s Paris is meticulously ordered, with rigidity masked as efficiency. It would be facile, however, to simply call Jacques Tati’s PlayTime just a satire of modern urbanisation.

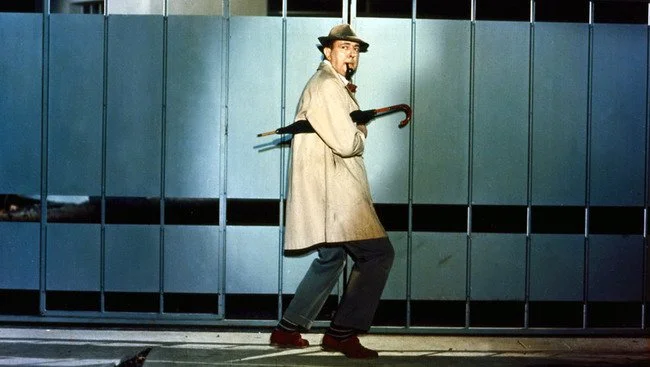

The film loosely follows the clumsy Monsieur Hulot as he bumbles through the modern maze of Paris that Tati constructs out of symmetrical, brutalist architecture. It’s a chaotic film where the quirky actors weave through these urban landscapes with humorous intent.

Monsieur Hulot is a recurring character in Tati’s films. He’s a character with a good-natured but clumsy disposition, representing the everyman in Parisian culture. A meek individual who dons his overcoat, top hat and pipe, he usually finds himself perplexed by the ridiculous scenarios he finds himself in, and Tati makes the most of the physical comedy in his films.

Nevertheless, following the success of his previous film Mon Oncle, Tati was becoming increasingly disillusioned with the straightforward presentation of comedy around one central, lovable figure. As such, PlayTime was made with little rhyme or rhythm to its structure. There’s a distinct lack of a singular focus, and Monsieur Hulot is decentralised as the protagonist. He becomes one with the city and the crowd that weaves through their technological urban environments, effectively rendered to the periphery and the margins.

His decentralisation is evident in the first act of the movie. Monsieur Hulot attempts to meet with a business partner, whom he continuously chases after amidst the partner’s hectic schedule. The brutalist symmetry of the building offers no guidance, and Hulot is shoved by the crowds into different facets of the building, diverted into identical corridors and rooms in his comical chase. It all eventually culminates in a scene where Hulot spots the man in a staff room. Here, Tati’s mise-en-scene presents these identical cubicles with a top-down perspective, as all the actors are clacking away at their keyboards, and Hulot wobbles through these endless labyrinths in his unavailing chase. It’s an overwhelming, overstimulating experience, with blink-and-you’ll-miss-it visual gags filling the frame. Hulot merely exists within the frame rather than being a focal point. Yet, despite its humor, there’s an immense, cold distance, amplified by the top-down perspective which denies the viewers intimacy. A visual representation of the isolation of modern urbanisation and how it can strip away individuality and create distance.

Even within the frame, we see employees communicating via landlines rather than engaging in physical conversations despite being seated mere metres apart, exposing the absurdities that are masked beneath technological progress. Such moments bear similarities to our daily Singaporean lives as well, where most corporate offices rely on internal messaging systems regardless of their employees’ physical proximity with each other. This isn’t to say that technology has no benefit, in fact it is quite the opposite. But rather, perhaps progress has traded the human aspect of communication for optimisation.

Modernisation and progress are further satirised when Tati shifts his focus towards a group of American tourists, who are enamoured the moment they enter an industrial departmental store. Gag products are displayed, such as a door which slams in silence, and a broomstick with lights on the bottom. These products make a mockery of modern invention, as innovation is conflated with ostentatiousness. Appearance is more important than efficiency, garnering appraisal from the American onlookers. The idiocy of these products creates more room for Tati’s comedy to be fully realised, as we reckon with our superfluous obsession with aestheticism.

In the most complimentary way, Tati’s metropolis is dull. There’s an explicit emphasis on cool colours, specifically blue and grey, with little to no contrast in these sterile walls of steel and glass landscapes. Tati continuously renders human presence secondary to systems of order and artifice, furthering a sense of detachment. He reinforces this by denying the audience any close-ups of our characters, presenting this broad scale of dehumanisation. The only remnant of nature is seen through a roadside flower shop, which a tourist becomes enamoured with, becoming a meagre symbol of tradition and organic life that struggles for preservation. Progress is a hollow facade, as Tativille reduces its characters to mere cogs in a machine, mechanised and engineered.

At this stage, the title PlayTime feels almost ironic. Joy appears absent, replaced by repetition, order, and emotional restraint. The visual gags so far had only elaborated on the overwhelming, isolating modern world, with ostensibly little connotation of joy or play.

However, Tati then subverts his own film, as the standardised symmetry becomes replaced with full-fledged chaos. This is where PlayTime moves beyond being a satirical piece. Monsieur Hulot, the American tourists and other wealthy Parisians all coalesce at a newly opened hotel restaurant. The staff all strive towards creating a perfect opening night, but the party soon erupts into a beautiful cacophony of human chaos. Walls and ceilings begin to fall apart, the chairs leave marks on the customer’s clothes, but they all continue dancing the night away, with the jazzy, circus-like music beating on. The mechanisms of modernity fail, but this gives way to liberation. The party becomes a representation of our inherently imperfect humanity, and how attempts to homogenise and perfect our lives — in line with our architecture and our consumer products — are ultimately futile. In all, Tati reframes this chaos instead as uncontainable beauty, a dazzling spectacle of our humanness, even as the modern world ticks on.

PlayTime is a remarkable film. Not because it is a laugh-out-loud slapstick satire, but because of the indescribable joy that forms in the face of spontaneity. The future can be bleak in how we navigate the spatial, temporal and relational. However, even as we negotiate our way through the confusion, the vibrance of the human spirit is simply unable to be contained.

Despite hailing from the late sixties, the film still sees relevance to our Singaporean landscape, as we continue to question the rapid modernisation of our homeland. The brutalist landscapes in the film parallel Singapore’s architecture, which tends to place emphasis on economic propensity, as seen from buildings in the CBD and their high-rises’ steely exteriors. Even spaces for the arts, such as The Esplanade, encouraged “profit making theatre” over individualistic expression in order to recoup heavy financial investment. As the city continues to prioritise efficiency and order, which is all well and good, Tati reminds us that beauty lies not in flawless design but in the messiness and disorder that occurs in our humanity, reclaiming space for connection and improvisation. Perhaps in Singapore, such moments can emerge organically in third spaces, which reminds us why it is so crucial to preserve them. In the pursuit of perfection, we must not forget to leave room for being human.

PlayTime was screened as part of the first half of ArtScience Cinema’s Visions of the Future programme. The second half runs from January to early February 2026. More about the programme on their site here.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021.