Review: SYFF’s Programme 2 & 3: Can You Hear Me?; Out of Nowhere

Editor-in-chief Goh Cheng Hao examines the programmes Out of Nowhere and Can You Hear Me? from the incoming SYFF, tracing the resonances within its varied narratives. If these films represent our current milieu, what concerns or anxieties might they reflect?

This review Has very, very, minor spoilers.One of my absolute favourite buzz-phrases to say is that I’ve got my finger on the pulse of the zeitgeist. An idiom from the wretched pits of film-cum-art-speak, it’s as unnecessarily affected as it is clothed in pseudo-intellect. A marker of importance milked so widely that it ends up not really saying anything at all; a poetics without the actual poetry. In that light, it’s kind of charming, really. It endears the invisible underpaid intern beefing up their copy with clumsily borrowed language.

But, for a moment, say we entertain the needlessly figurative language: what truly is the diagnosis here? Directed toward our contemporary film scene where the phrase often orbits, how is the scene doing? Are our creative juices flowing in healthy rhythm, or are their veins clogged and calcified? What is the defining spirit – as -geist translates to in German – of our local film microbiome? We might get a sense through the Singapore Youth Film Festival’s (SYFF) programming this year.

In their second edition since 2024, SYFF returns to spotlight the younger generation of voices in filmmaking. This year, it organises its programming under the thematic framework of Focus, Gather, Bloom, gathering forty-three films under nine programmes in the latter.

Of which, Programme 2 is titled Can You Hear Me?. While it’s obviously interested in the voices and stories that are inaudible, more importantly, it implores us to lend a listening ear to them. It asks: what might listening entail, especially in a world in which the most vocal gets the last say, and where loudness becomes authority? We’ve seen how free speech rarely facilitates dialogue. But on the other hand, listening is receptive. When one listens, he isn’t speaking. Others are then heard without interruption. Listening lets us understand the unfamiliar; listening is a radical act. This need for receptivity and understanding is seen precisely in the generational (and otherworldly) miscommunications of Jerold Lim Xing Jie’s One Last Supper and Aram Winter’s Open House; likewise in the cryptic messages in Angela Chan Ying Ki’s 961081. The sentiment, however, resonates most strongly within the films that bookend this programme – Tan Ning Xuan’s I Think I’m Going to Die, and Ben Tan Kai Xiang and Grace Cheu Li Qing’s Mountain Mountain.

I Think I’m Going to Die looks at the ailing body through a variegated blend of mixed-media animation, a mode that echoes the convoluted experience of both womanhood and illness. And with its many visual metaphors, it recalls the arguments surrounding the metaphoric thinking of illness, not just in the ways in which it is often rendered taboo, ‘unclean’, or even as punishment, but also the figurative language in which we describe it: the militant ‘to battle’ or ‘combat’ a disease. It is that metaphors are two-pronged. They translate the abstract experiences of illness known only to the persons they belong to, but they also perpetuate the shaming and abjection of said bodies. How then should we talk about these things? What does illness mean to us?

In line with the festival’s ethos on platforming new voices, how might the ailing body rendered mute, speak for itself, and also speak against the language imposed onto it? Most of all, as the programme proposes, how best might we listen or respond? I Think I’m Going to Die jostles with these prickly questions.

Mountain Mountain carries on the tail-end of this train of thought. Behind its fuzzy and comfortingly homebrewed animation, it sits, on its hands, with the same sobering awareness of impending change and the nauseating uncertainty that follows.

A small but poignant bit at the crux of Mountain Mountain is the proclamation: “山上有人吗?” (“Is there anyone on the mountain?”), as uttered by one of its characters. It starts off as an innocent vocal exercise, but as it echoes within the empty space around it, its anxiety compounds upon itself, swelling, reverberating, amplifying and expanding finally into a more disquieting question: strain as you might to let yourself be heard, but what does it matter if there’s no one out there to listen at all? Is there anyone out there? A feeling of loneliness and company aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. The crowded world has never felt so cold.

These two films are shot through with a muffled scent of despair, seeping through the three other shorts — themselves equally notable and impressive — sandwiched between them, but felt most audibly at its ends. What Programme 2 then proffers in response then is less about finding the ‘right’ answer to a cry for connection as we might be conditioned to. It is that we might not need to completely understand or empathise with somebody to care for them. Empathy, as it stands, is also often misguided and presumptuous, redirecting attention away from the person who needs it most – how could I possibly know and understand all depth of your feeling? Something so simple as being there to listen, however, and listening curiously, is enough.

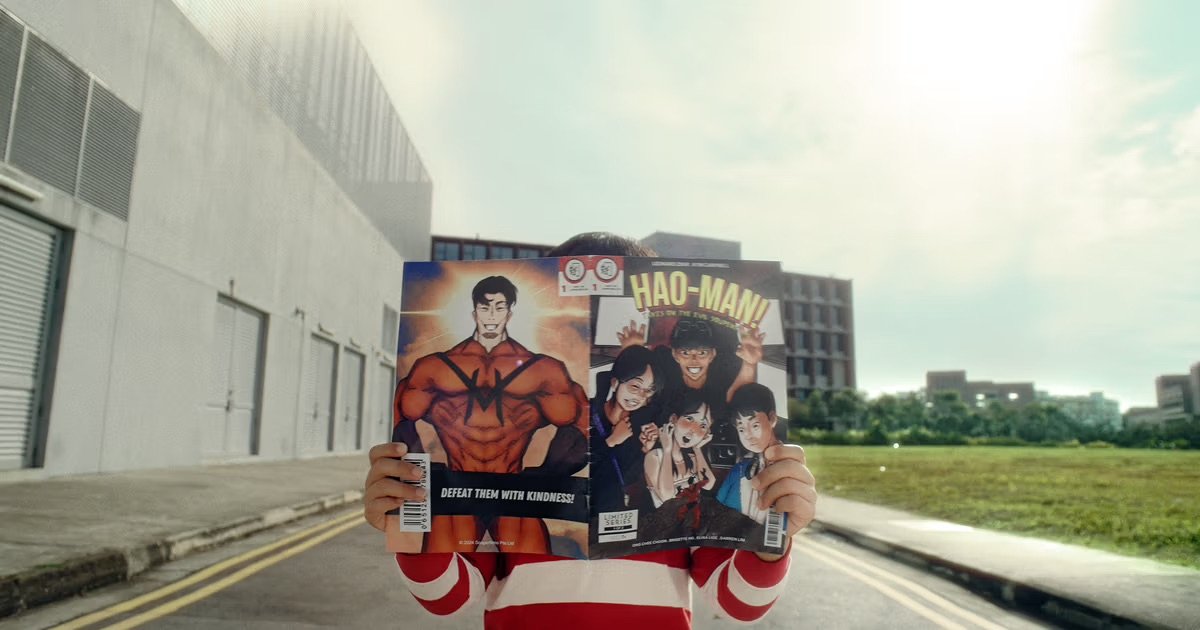

And if Programme 2 surrounds the things that go unheard, Programme 3 feels like an appropriate companion piece, for it charts the inner worlds these feelings often conjure. Titled Out of Nowhere, the programme centres the mind and its dual power of imagination and illusion. Admittedly though, imagination feels like a disappointingly generic thread to weave through the motley assemblage of shorts – shouldn’t all films, in line with what imagination might mean, tell a novel story or perspective, and do so creatively? – of which Pan Wenbo’s refreshingly off-kilter and eye-numbing 梦游神 (Meng You Shen), Ong Chee Choon’s whimsical comic Hao Man, and Valerie Theodas’s zany, radioactively exciting sci-fi Last Supper easily fall under, but nevertheless still radiate promising imaginative potential.

L to R: Pan Wenbo, 梦游神 (Meng You Shen); Ong Chee Choon, Hao Man, Valerie Theodas, Last Supper. Images from SYFF.

Illusion, however, the more intriguing motif of the two, materialises starkly in Azina Binte Abdul Nizar’s We Learn to Breathe in Distant Places. In the form of hallucinations and apparitions, illusions exist as an unnerving proposition of what ends the mind is capable of; it illustrates the mind’s fallibility and its willingness to warp our perceptions of reality to cede to our (sub)conscious desires. It is not just about self-deceptions, but also ones that are imperceptible from real life, and that lure you in with false hope. That kind of indiscernible threat is greatly unsettling.

About a housewife in the wake of her son’s unexplained disappearance, Distant Places follows her search for resolution. As she ventures into the forest, the boundaries between reality and illusion seem to collapse, and they begin melding into each other. This merge is most reflected in the film’s treatment, one of its more notable aspects. A call back to analog aesthetics – the nostalgia for which likewise evokes a feeling of fondness – halation and grain blurs the contours of the film’s subjects and environments, creating a soft, dreamlike haze. It tinges the light a downy, gauzy pink, opposite to Apichatpong’s hostile, cold, and steel-blue renderings of the forest in Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. But this facade of warmth and welcome, unfortunately, masks but a hollow mirage. Whether intentional or not, the visual allusion to these delusions makes Distant Places a haunting watch. The otherworldliness of the story, much like Suzuki’s Ring, eerily begins to possess the film itself.

What does Out of Nowhere tell us then, and in conversation with Can You Hear Me? – what strings both programmes together is the idea of connection, or the lack thereof. Whether it be the interpersonal in the former, or with broader concepts of identity in the latter – the national, cultural, or vocational – the films in these programmes reveal a constant grappling with connection and lucidity. Returning to our doctorly analysis, if they are to diagnose our contemporary milieu, perhaps they express a younger generation’s attempts to make sense of and connect with a meaningless world, an act that, as it goes, we might all be able to relate with in some way. It is not just that the world is increasingly at odds – there is an awful amount of homogeneity and conformity as well – but it is about where there might be an absurd lack of meaning in life, when it is exposed to be full of artifice and disconnection (remember the zeitgeist-speak; empathy; illusion).

These insights, however, only emerge on the credit of SYFF’s thoughtful programming. With nine reasonably curated and substantiated programmes – which read more intentionally and deliberately than those of most other festivals – the conversations generated between the varied films within seem to be particularly coherent. So if SYFF is all about the voice, there is undeniably a diversity, and though they might babble and mumble at times, if you take the time to pause, and to listen to their stories, you might just be able to make out the burgeoning wants of contemporary filmmakers and programmers alike.

SYFF’s Programme 2 and Programme 3 screen on 30 January, Friday at 8:30pm, and 31 January, Saturday, 8pm, respectively, at SOTA Studio Theatre. Get your tickets here.

Images in this article are being used under Fair Use guidelines as part of Singapore's Copyright Act 2021.